Back to square one in Syria

Thirteen years and eight months of war, nearly half a million deaths, millions of refugees, relentless clashes, and widespread destruction... As of November 27, Syria has entered yet another turning point in its conflict.

Jihadist groups led by Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), along with factions from the Turkey-backed Syrian National Army (SNA), launched attacks against the Syrian army in western Aleppo and southern Idlib on November 27. Within a week, these forces captured over 8,000 square kilometers of territory.

The operation, dubbed “Deterring Aggression” (Rad’ul Udwan), included not only HTS but also groups such as Ajnad al-Kavkaz, Muhajireen and Ansar Brigade, and the Turkistan Islamic Party, composed of fighters from Central Asia, the Caucasus, and various Arab nations.

Among the Turkey-backed SNA factions involved in the offensive were the Sultan Murad Division, Hamza Division, Suleiman Shah Division, Ahrar al-Sham, Faylaq al-Sham, Suqour al-Sham, Northern Storm Brigade, Nour al-Din al-Zenki Movement, National Liberation Front, Jaysh al-Izza, and the Sham Front.

HTS had been preparing for this offensive for a long time. The London-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR) had previously highlighted these preparations.

According to an SOHR report dated Aug 4, HTS leader Abu Mohammad al-Jolani held a meeting with the group’s military and security commanders to discuss the possibility of a conflict between Israel and Iranian militias on Syrian or Lebanese soil. The HTS leadership analyzed the opportunities such a conflict might create and focused on planning an attack against the Syrian Army.

During the meeting, they outlined strategic goals, including seizing towns and villages along the M5 highway connecting Damascus and Aleppo, defending villages in southern Idlib and northern Hama, and exploring the possibility of reaching Aleppo city if conditions allowed.

That possibility became reality. In the early hours of November 30, HTS and its allies captured Aleppo, Syria’s second-largest city. The HTS-SNA offensive also exposed critical vulnerabilities in Syria’s military and security infrastructure.

The reasons behind the collapse within the Syrian Army

In nearly 14 years of war, Aleppo’s city center, international airport, and key military facilities had never fallen into the hands of jihadist forces. Yet, HTS-SNA achieved in mere hours what might have otherwise taken years.

Much has been written about the support provided to jihadist groups. The impact of advanced weapons, ammunition, equipment, and kamikaze drones is evident. However, attributing the Syrian Army’s situation solely to a "tactical withdrawal" would be insufficient.

South Front, an “independent intelligence-analysis site” focused on conflicts in the Middle East, particularly from a Russian perspective, made noteworthy observations about the rapid collapse in Aleppo.

According to South Front, intelligence about the impending attack had been relayed to Damascus via the Russian Ministry of Defense as early as August. HTS began conducting tactical assaults in September. Despite these warnings, the Syrian Army and Iran’s Revolutionary Guards took no significant countermeasures. Defensive fortifications along the Aleppo frontlines were not strengthened, troop density remained low, and there were no consistent minefields or fallback positions.

The “most serious and ongoing issue” facing the Syrian Army is its severe manpower shortage. South Front reports that active units face a 40% shortfall in personnel, which can rise to as much as 60% in some cases.

The most striking point in the analysis is this:

The motivation of SAA soldiers and officers is extremely low, whilst material support is at a very low level. This has led to numerous acts of extortion by the military against the local population. The authority of the authorities has been seriously undermined by outright extortion by the military. The M5 highway between Aleppo and Damascus has been illegally taxed, as in the Middle Ages; it has become impossible to pass without paying a bribe. Thus, undertaking military service has become a business. The situation has been exacerbated by ethno-religious differences between the local population and the troops. The Syrian Arab Army is half Alawite, and among the officers, there are even more Alawites, which is anathema to the Sunni majority. With an average salary of 20-30 dollars, Alawites in Syria receive significantly more.

Speaking to Middle East Eye, which is funded by Qatari capital, unnamed “senior Turkish security sources” pointed to this general disarray as a key factor: “This attack, initially planned as a limited operation, expanded when regime forces began fleeing their positions.”

In addition to these internal issues, external factors have also contributed to the Syrian Army and its allies' weakening. Russia’s focus on Ukraine and recent regional developments—Gaza and Lebanon wars—have played a role.

One significant factor is the withdrawal of Hezbollah forces from Syria to Lebanon in response to Israeli attacks. This alone has had a notable impact on the situation on the ground.

The regional equation impacting Syria

One of the key lessons from nearly 14 years of war in Syria is that this region leaves little room for "coincidences."

After 56 days of ground warfare, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu failed to force Hezbollah to its knees in Lebanon and accepted a fragile ceasefire brokered by the United States. On November 26, as he announced the ceasefire on camera, Netanyahu pointed a finger at Syria:

“We are systematically preventing Iran, Hezbollah, and the Syrian Army from supplying weapons to Lebanon through Syria. Assad must understand he’s playing with fire.”

It is no coincidence that HTS-SNA launched their offensive the very next day. While this sequence of events requires further explanation, for now, let’s proceed with what we know.

On September 23, Israel began its attacks in Lebanon and simultaneously ramped up airstrikes on Syrian soil. The impact of these strikes has been severe.

On November 20 alone, airstrikes targeting the city of Palmyra (Tedmur) in Homs province killed 105 individuals, including Syrian Army soldiers and their allies. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights documented 160 Israeli attacks on Syria between the start of the year and December 3.

These strikes targeted military positions, headquarters, and arms depots across Syria. The toll included:

- 64 Syrian soldiers,

- 59 Hezbollah members,

- 25 members of Iran's Revolutionary Guards,

- Over 200 Iranian-backed militiamen.

In total, 416 individuals were killed, and 286 were wounded.

Meanwhile, U.S. forces also conducted a series of attacks against Iranian-backed forces in Syria's Deir ez-Zor province, near the Iraqi border.

Both Israel and the U.S. claim these strikes are part of efforts to counter Iran’s influence in the region. These operations continued even after HTS-SNA began their offensive on November 27.

The chaos and clashes in northwestern Syria soon spread eastward. In Deir ez-Zor, the Deir ez-Zor Military Council, an affiliate of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), launched operations against the Syrian Army and Iranian-backed militias with air support from the U.S.

To the south, the U.S.-backed “Revolutionary Commando Army,” stationed at the Syria-Iraq-Jordan border triangle, began preparing for an attack in the Deir ez-Zor region. Simultaneously, areas such as the outskirts of Damascus, Daraa, and Sweida appear to be likely targets of coordinated operations involving Israel and armed factions.

Ankara made a choice

In Syria, it was essential to negotiate with powerful actors like Russia and Iran. This led to the Astana process in 2017. However, when these powers weakened for various reasons, it was Ankara that effectively dismantled the table.

On November 15, Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan stated in a televised interview that while the Astana process had frozen the Syrian civil war and reduced casualties and displacement, “the necessary steps for a better solution were not taken.” He criticized Damascus for failing to amend its constitution to facilitate the return of Syrian refugees abroad and to establish common ground with opposition groups. He also lamented that Moscow had not exerted “enough pressure” on Damascus to make these changes.

But throughout this process, did Ankara fulfill its own obligations?

Under the Sochi Agreement of September 17, 2018, Turkey was tasked with distinguishing HTS from other armed groups. This was never achieved. Despite the establishment of dozens of observation posts in Idlib and surrounding areas, attacks could not be prevented. Instead, HTS continued to institutionalize and grow militarily.

Now, we face a situation unfolding with Ankara’s overt approval: an “Islamic Emirate” that has expanded its dominance around Idlib and seized numerous strategic points, including the city center of Aleppo.

About Idlib and HTS

Idlib is a region burdened with the accumulated and deferred crises left by all the countries—including the AKP government—that have fueled the war in Syria since 2011. It is home to jihadists who have gained power through various forms of support, civilians forced into refugee status and used as bargaining chips against the West, and soldiers whose deaths are politicized.

The jihadist umbrella group HTS (Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham), which originated as the Syrian branch of al-Qaeda under the name Nusra Front (later “Jabhat Fateh al-Sham”), was established in January 2017. Since November 2017, HTS has governed Idlib through its political arm, the “Syrian Salvation Government.” Although Turkey officially recognizes HTS as a “terrorist organization,” the group continues to wield control in Idlib.

Despite cooperating in the Aleppo offensive, HTS and the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA) differ fundamentally. HTS operates as a more centralized and institutionalized entity, while SNA factions have been accused of opportunistic behavior. This led to a major conflict when HTS arrested members of the SNA over accusations of “looting.”

While the SNA has criticized HTS for its “aggressive stance,” such condemnation carries little weight on the ground. Historically, these groups have oscillated between cooperation and conflict. For example, they jointly captured Idlib in 2015, but over time, HTS either absorbed or subordinated other factions, consolidating its dominance.

Under the current conditions, a similar scenario seems likely. Disputes over the control of Aleppo and other strategic points will continue to be sources of persistent conflict between the two sides. Yet, in the long run, HTS is expected to maintain its dominance, further strengthening its “Islamic Emirate.”

The Aleppo offensive and the Kurds

The capture of Aleppo by HTS and the SNA also determined the fate of the Shahba region, which includes Tel Rifat and its surroundings to the north. This area, controlled by the Syrian Army and Kurdish forces and often referred to as the “northern gateway to Aleppo,” was abandoned in parallel with the retreat from Aleppo. SNA militants captured the region as part of their offensive titled “Dawn of Freedom” (Fecr al-Hurriya).

Tens of thousands of people, including many Afrin residents who had sought refuge in the region after the 2018 attacks, were displaced once again and forced to move to areas under the control of the Autonomous Administration.

The fate of Sheikh Maqsoud and Ashrafiyeh, two Kurdish-controlled neighborhoods in northern Aleppo, remains unclear. HTS issued a statement directed at Kurdish forces, demanding they “withdraw safely with their weapons.” However, reports indicate that negotiations between the parties are still ongoing.

The record of jihadist groups in similar “evacuation” scenarios is marred by violence. For example, on April 15, 2017, a vehicle bomb targeted Shia-majority civilians being evacuated from the towns of Foua and Kefraya in Idlib’s countryside, killing more than 126 people, most of them children. While no group claimed responsibility, the method of the attack and the targeting of Shia civilians pointed to jihadist factions.

Sources close to the Damascus regime report that the shock caused by the events in Aleppo has been partially mitigated thanks to warnings and support from Moscow and Tehran, especially as the conflict spreads toward Hama. However, fierce fighting continues on the outskirts of Hama.

At the same time, Kurdish forces are preparing for a potential new SNA offensive targeting Manbij.

These developments in Syria pose serious challenges not only for the Damascus regime, its allies, and Kurdish forces but also for the entire region. The growing presence of jihadist groups, flourishing right on Turkey’s doorstep, threatens not only Syria but also the broader region with greater destruction, more deaths, and an unending cycle of war.

According to SOHR data dated Dec 4, the death toll in the region rose to 704 due to the clashes and airstrikes following the HTS-SNA attacks launched on Nov 27:

- 302 members of HTS,

- 59 people belonging to groups affiliated with the SMO,

- 208 Syrian soldiers, including 23 officers, and 25 Iranian-backed militias, including 10 Syrians and 15 foreign nationals,

- 15 civilians in HTS attacks,

- Russian and Syrian ground and air strikes on Aleppo and Idlib killed 88 civilians.

(VC/VK)

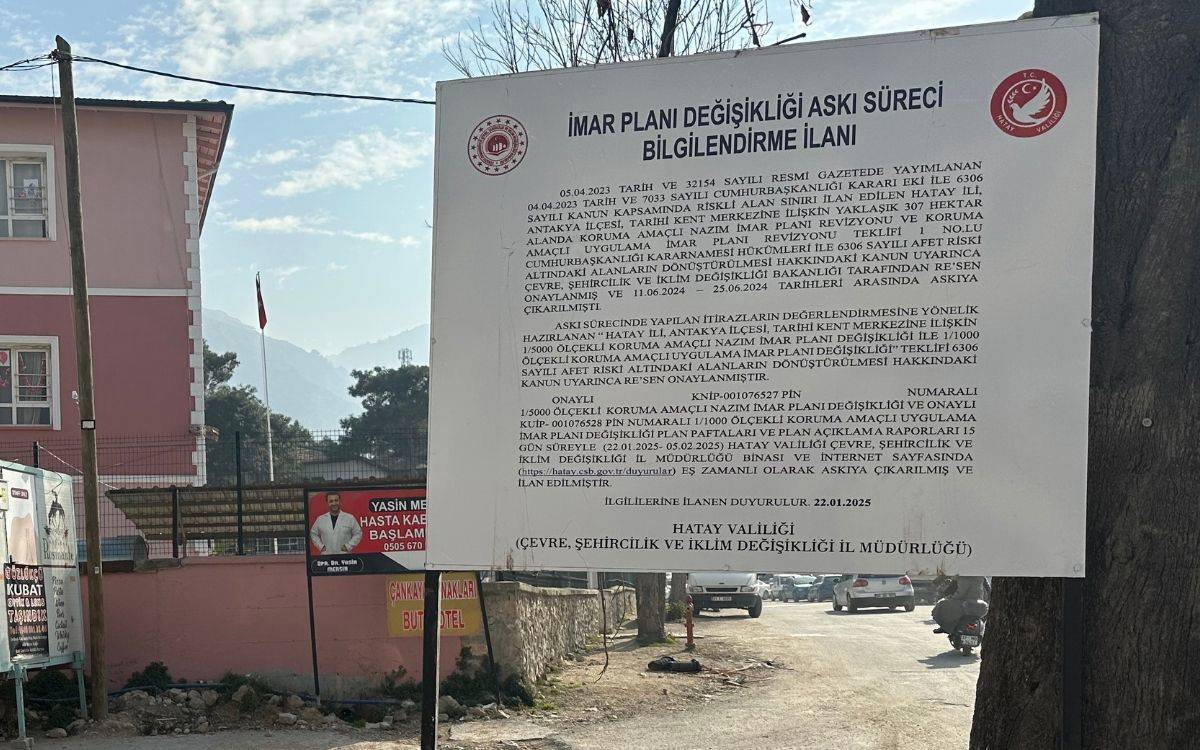

Forced land seizure in Hatay: 'We survived the earthquake, but the government is killing us'

Erdoğan shows protest footage from Georgia in speech targeting İmamoğlu protests

WITNESSES OF THE SAHEL MASSACRE

Zaynab from Latakia: We just want to live in security and peace

ANNIVERSARY OF FEB 6 QUAKES

The never-ending 'temporary' life in a Hatay tent city

Two years on from Turkey earthquakes: Who is the Antakya protection plan protecting?