ANNIVERSARY OF FEB 6 QUAKES

The never-ending 'temporary' life in a Hatay tent city

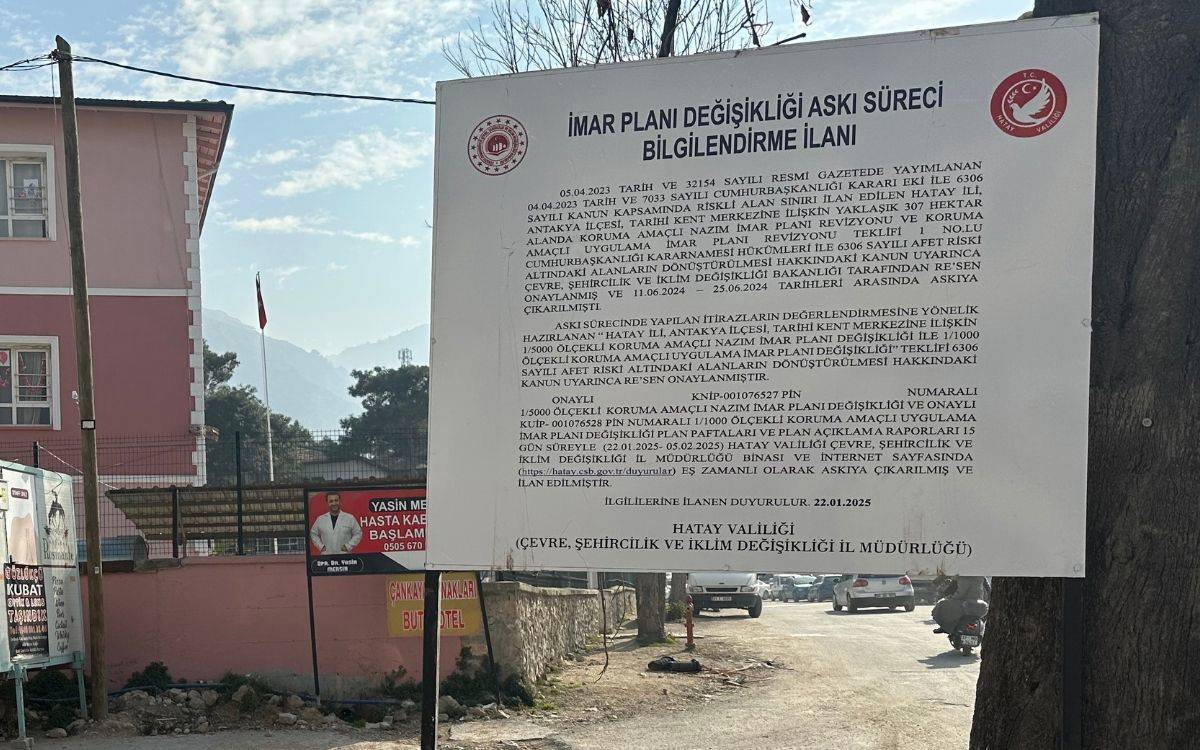

As the second anniversary of the 2023 earthquakes comes, Antakya remains far from its former vibrant days. Dust and smoke hang over the city, mingled with the constant noise of machinery and trucks. Despite being referred to by officials as "the world’s largest construction site," the most critical problem after two years remains unchanged: housing.

"Temporary" living spaces have become mentally ingrained as permanent. According to official reports, there are 204 container settlements. A total of 223,906 people still live in containers—177,165 in organized container settlements and 46,741 in individual containers. For two years, everything about daily life has had to fit into just 21 square meters.

While following up on life in these container settlements, I come across information about the "Kyrgyz Tent Camp."

Located in the Koçören neighborhood of Defne, along the Antakya-Samandağ road, the camp is about nine kilometers from the city center.

Former AFAD (Disaster and Emergency Management Authority) President Okay Memiş shared a post on June 8, 2023, mentioning their inspection of the Kyrgyz Tent Camp in Koçören. He noted, "In a settlement comprising 198 tents, each 21 square meters in size and five meters tall, the infrastructure has been completed, and most of the tents have been set up."

At that time, news reports stated that these tents would serve as a "temporary yet new home" for residents. Today, approximately 150 families continue to live in the camp, most of whom come from various neighborhoods in Defne, the district hit hardest after Antakya.

Rubble and new constructions

Koçören, also known locally as Mengüllü, became a focal point shortly after the earthquake due to discussions around rubble dumping sites and emergency expropriations.

Residents protested against rubble disposal areas and the rapid expropriation of lands near residential areas and olive groves under disaster housing projects.

'We didn’t want to leave our neighborhood'

I came across Hasan as he was inspecting his car with the hood open. A simple greeting led to a conversation. His disappointment became clear from his first sentence:

"Unfortunately, our hopes are fading. You see how it is—promises like 'your homes will be ready in a year' and so on. [Pointing to his tent] I’ve been staying here with my wife for two years now, still waiting for my house to be rebuilt."

I ask about his house. "It was right here," he says, pointing to an empty lot next to the camp. "We didn’t move to a container camp because we didn’t want to leave our neighborhood or give up our land. Our house was destroyed. My son brought a container here and pieced something together for us. We're surviving somehow."

Living a temporary life

I ask him about life in the tent camp. Hasan starts by noting that they are classified as living under “container status.” However, this status doesn’t mean the conditions are ideal. He goes on to describe their daily struggles.

"We have electricity, water, and bathrooms. But the electricity often cuts out. Sometimes it goes out three times a day, sometimes it’s gone for five hours straight," he explains.

Water issues are another challenge. "Sometimes the pipes burst. We report it, but no one comes for two or three days. They bring water in from tankers and tell us, 'Use it sparingly.' So, we’re living this temporary life."

'Not suitable for long-term living'

According to the second-year report released by the Hatay Earthquake Victims Association on February 3, container settlements across Antakya are not fit for long-term living. The report highlights structural issues, flooding, frequent power outages, and a lack of social amenities as the main problems. The Association states that the government has failed to improve these areas into more livable temporary spaces, leading earthquake survivors to endure harsh conditions for the past two years.

Living on pension

Hasan spent years as a truck driver. "I delivered goods to 40 countries, including in Europe," he says with pride. But now, he struggles to make ends meet on his pension.

When I ask his age, he jokes, "Not 69—19." Yet his face reveals the exhaustion and uncertainty of the past two years.

"I was a working pensioner," he explains, summing up his recent experience: "My pension isn’t enough. I tried once—I said, ‘Let’s see how it goes if I stop working.’ My friend, my monthly income barely lasts 12 or 13 days. After that, it's gone. I was still working when the earthquake hit. Now I'm trying to live on my pension again. But what can I do with just this?"

'They even think this junky car is too much for me'

During our conversation, Hasan turns to his car, placing a hand on it as he speaks:

"This is my only other possession—this old clunker. It’s an ‘86 model. It gets me from point A to point B, but even this is too much for them. They say, ‘You don’t qualify for the Esen Card [a 4500 lira aid card provided by the Red Crescent] because you have that car.’ I ask, ‘What’s so strange about it? Should I just dump it in the trash?’"

'A lottery is drawn, but there’s no house'

I ask Hasan if the Koçören TOKİ buildings have been completed. He sighs and replies, "No, they’re not finished yet. There are still some details to take care of, but I have no idea how much longer it will take."

Hasan explains that being assigned a house through a lottery doesn’t guarantee much. “They tell some people, ‘This third-floor apartment in such-and-such building is yours.’ So, they go to see it. The place is just a rough construction—unfinished. No electricity, no windows, no tiles. But the lottery says it’s theirs. Look, I don’t just want a lottery—I want a house, a home where I can live."

He mentions that about ten days ago, two officials from the District Governor's Office visited the tent camp to ask if there were any unmet needs. "I told them, ‘Yes, we need something. We need a house,’” he says with a smile.

Destruction and reconstruction in Hatay by the numbers

In a statement on February 4, Hatay Governor Mustafa Masatlı reported that 40% of the buildings across the province had become unusable due to the earthquake, with over 88,400 buildings demolished and the debris of more than 327,000 individual units cleared.

Following the February 6 earthquakes, the government announced a target to build 319,000 new homes across 11 provinces within one year. By the end of the second year, 201,580 homes had been delivered. In Hatay alone, 46,167 units have been handed over, including 40,586 residential units, 27 businesses, and 5,554 village homes.

According to a February 3 statement by the Ministry of Environment, Urbanization, and Climate Change, the goal is to deliver 153,248 homes and businesses in Hatay to their rightful owners by the end of 2025.

(VC/VK)

Forced land seizure in Hatay: 'We survived the earthquake, but the government is killing us'

Erdoğan shows protest footage from Georgia in speech targeting İmamoğlu protests

WITNESSES OF THE SAHEL MASSACRE

Zaynab from Latakia: We just want to live in security and peace

Two years on from Turkey earthquakes: Who is the Antakya protection plan protecting?

Turkey’s last Armenian village faces expropriation threat