Military Court Defies Medical Science

In its detailed final decision related to the landmark case, the Court of Appeals referred to Tarhan's refusal of being physically examined to establish his homosexuality and said that under the circumstances, a correct course of action would not be a forced examination, but recruiting him into military service.

Tarhan (27) first voiced his conscientious objection to military service in October 2001 and has been detained twice since and spent time in prison. Tried in August last year, he was given a prison term of two years for each of the two charges of insubordination leveled against him, totaling to four years.

"I... refuse to be transformed into a murder machine by taking a course in dying and killing," Tarhan told a court during his August 2004 defense.

Science versus mentality

"Homosexuality is a sexual identity that approximately 15 percent of the people share" said Union of Turkish Physicians (TTB) deputy chairman Metin Bakkalci critical of medical science being used for other purposes in light of the Military court decision.

Can Cimilli, the deputy chairman of the Turkish Psychiatry Association, emphasized that current literature did not regard homosexuality as a disorder and that current legislation described it as "a life style, a preference". He added, "its just like being blond".

Former chairman of the Istanbul Chamber of Physicians (ITO) Gencay Gursoy accepted that in an environment of scientific discussion, any issue could be debated adding, "but in a judicial procedure directed at an individual, it is extremely interesting to see a condition such as this which has nothing to do with medical science being made an issue".

Tarhan has from the very beginning refused to undergo a physical examination which would prove or disprove his homosexuality.

Cimilli: For psychiatrists homosexuality is like being blond

Cimilli explained that in current literature with regard to homosexuality the American Psychiatric Association (APA) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) were fundamental resources and neither regarded homosexuality as a disorder.

The situation is the same in the World Health Organisation International Classification of Diseases (ICD) test.

"In current literature" Cimilli said, "homosexuality is not regarded as a disorder... It is like being blond."

Referring to the same texts, TTB's Bakkalci told Bianet that "in order for a condition to be classified as a disease, its basic definition needs to be made. There is no such definition for homosexuality."

Bakkalci: In contradictory cases we have the authority

When asked what it would mean professionally if the armed forces in Turkey were to conduct examinations to establish homosexuality and diagnose it, Metin Bakkalci said the following:

"We place great importance on the basic principles of our profession being valid everywhere to protect the health rights of individuals. Where there are practices contradictory to this and applications based on data are made, we will take those into evaluation."

Bakkalci said wherever doctors carried out their practice, whether in the army or public sector, the TTB had the responsibility of monitoring them and continued:

"In February with the Interdepartmental General Commission of the Council of State, debates on this issue ended. In whichever field they conduct their practice, the process of evaluating the professional conduct of our colleagues is under the TTB's responsibility".

Bakkalci recalled that the TTB was the only body authorised by law in this field in Turkey and said that if doctors violated the principles of their practice, they could be penalized in many ways ranging from a caution to six months suspension from practice.

Military Court reference contradictory

In its detailed verdict dated March 9, 2006, the Interdepartmental Commission of the Military Court of Appeals referred to homosexuality being listed in the Turkish Armed Forces Health Regulations among "psychosexual disorders and advanced stage psychosexual disorders" stating these allowed exemption from compulsory conscription.

Though the order quoted articles 17/B-3 and 17/0-3 of the Regulation and cited the need to establish whether an individual was homosexual or not by military medics, no direct reference to "homosexuality" exists in the Regulation itself nor any annex listing disorders and diseases.

Articles relating to psychosexual disorders and advanced stage psychosexual disorders refer to concepts such as "sexual behaviour disorders" and "people with sexual behaviour disorders that can be observed in every part of their life" respectively.

Background of Tarhan Case

Tarhan, first voiced his conscientious objection to military service in October 2001.

"I think that wars caused by power-mongering states are first and foremost a violation of the right to life," he said at a press conference in Ankara. "The violation of the right to life is a crime against humanity... I therefore declare that I won't be an agent of such crime under any circumstances. I will not serve any military apparatus," he said.

Tried on 10 August last year, he was given a total prison sentence of four years on two counts of insubordination charges. Last November the Appeals Court overturned Tarhan's prison sentence on grounds that it was disproportionately high and therefore unfair, but its final written recommendation was that his homosexuality should be identified by "proper physical examination procedures".

Because Turkey doesn't recognize the status of "conscientious objector," Mehmet was legally seen as a deserter. But Turkey's policy of "ignoring" some 70 people, who have announced being conscientious objectors, changed on April 8, 2005.

In the 15-year-old history of conscientious objection in Turkey, three people have been charged with this offence. All three of them were released at different stages of different trial procedures. Although their addresses were known, none of the conscientious objectors were recalled to the army. This issue is Turkey's weakness. The state would never dare to let the conscientious objectors trigger a debate about the military or military service, which are both taboos in Turkey.

On April 8, when Mehmet refused to sign any documents at the Izmir Military Recruitment Office, the deadlocked bureaucracy let the incoherent legal system solve the problem. Mehmet was first transferred to the military corps in Tokat, then to the Sivas Military Jail. The course of his life sentence was thus drawn out.

Although Mehmet repeated on a number of occasions that he is a conscientious objector, he was charged with "insisting on disobeying orders in front of assembled recruits." He was attacked by prisoners who were provoked by the prison administration, he was blackmailed and threatened. Although he openly stated he is a homosexual, he was forced to undergo physical examinations.

Ten soldiers kicked and stamped him, and cut his hair and beard. He was locked into a solitary confinement cell. He began self-mutilation and a hunger strike to protest against discrimination and bad treatment. He also demanded that his conditions be improved.

He stood the third hearing of his trial on June 9. He was released pending the outcome. Because he was persistently referred to as a "soldier" he was sent again to the Military Recruitment Office, then to the corps, and then to prison. He ended his hunger strike after 28 days when some of his demands were met. But a day before his hearing on July 12, his hair and beard was forcibly cut again. (TK/II/YE)

KURDISH QUESTION

PKK Ceasefire to be Terminated on 31 October?

KCK CASE

Court Dismissed Request for Defence in Kurdish

7th Istanbul Gathering for Freedom of Thought

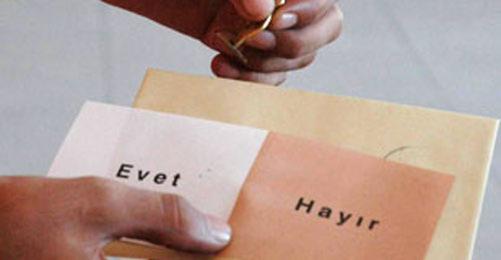

CONSTITUTIONAL AMENDMENTS

58 Percent Said "Yes" to Constitutional Reform Package

Rights Organizations 3 Years ahead of Foreign Minister