How Öcalan's call for PKK's disbandment echoed in Diyarbakır

In Diyarbakır, the largest Kurdish-populated city, people began gathering early around Dağkapı Square yesterday, eagerly awaiting PKK leader Abdullah Öcalan’s statement. The weather was warmer compared to previous days, with the sun shining brightly overhead. There was a Newroz-like excitement in the air.

Some were singing songs, while lively groups of young people laughed and chatted. Nearby, elderly women wearing white headscarves sat on the grass and benches, watching the crowd.

One of those women spoke to a journalist: “My daughter, I am a mother—how could I not want peace? How could any mother not want peace? I am hopeful. Today is a historic day for us.”

At Hürriyet Büfe in the square, people sipping tea speculated about what might happen: “Whatever step is taken for peace, let it be taken,” one said. Another added, “They say there will be a video today. We’ll finally see, inshallah.”

Some had traveled in from other districts, but many were frustrated at the last-minute notice: “There will be dozens of people missing out on such a historic moment.”

The excitement

As people started entering the square, older men who had positioned themselves on higher ground called out to journalists, pointing at different spots, saying, “Make sure to capture that, too.” After passing through two security checkpoints, attendees joined in with the music playing in the background, ululated, and embraced familiar faces. This kind of energy was usually seen during Newroz celebrations—Diyarbakır’s people were welcoming spring in high spirits.

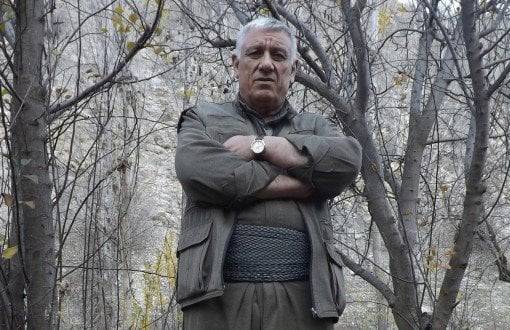

As time passed, the square filled up. People of all ages, from 7 to 70, arrived waving flags, dressed in their finest. Many older men wore traditional şal û şepik outfits. Banners passed from hand to hand across the crowd.

On a sidewalk, two young women stood with a little girl around 8 or 10 years old. Every now and then, the child would stand up and join in with the songs. The setting sun cast its golden light on them. The women chatted about the weather, reminiscing about how the sun had come out back in 2015 when Öcalan’s letter was read at Newroz.

Listening in on their conversation, the little girl turned to her mother and asked, “Mom, has spring arrived?” The women around them smiled, while her mother replied, “Yes, my daughter, inshallah, today spring will come.”

Silence falls as Önder begins speaking

As all this was unfolding, Sırrı Süreyya Önder’s voice suddenly echoed from the screen. The crowd fell silent. As Önder mentioned the imprisoned individuals who had fought for peace, the silence became even deeper—no one made a sound.

“We went to nurture hope. We went with the belief and determination to offer it breath and life together. We must nurture this hope.”

As people listened, a woman in a white headscarf translated his words into Kurdish for the others beside her. Holding hands, they strained to see the screen behind the barriers. They repeated each sentence to one another, nodding in agreement at every word.

Shock and confusion after Öcalan's message

Across from the group of women, a cluster of young people passed around the first photograph of Öcalan in 12 years, analyzing the seating arrangement of the delegation. Just as they were deep in discussion, an announcement came: the letter was about to be read.

As Ahmet Türk began reading the Kurdish version of the statement, some people sat down on the ground. Women who had started crying leaned on their friends for support, while elderly men tried to hide their tears. By the time the statement reached the call for “laying down arms and dissolution,” shock was evident on many faces in the crowd.

The reading ended with Öcalan’s signature, which was followed by applause.

More tears as the Turkish version is read out

Immediately after, Pervin Buldan began reading the statement in Turkish. The message seemed to sink in more clearly this time, as more people dropped to the ground in tears: “…all groups must lay down their arms, and the PKK must dissolve itself.”

Following the announcement, a large part of the crowd began moving toward the exits. As the square emptied, the full view of the gathering space became visible. Some of the Peace Mothers remained seated on the ground, others embraced those who were crying, and a few murmured, “Let’s wait and see.”

Three distinct emotions filled the air: a group of 20 to 30 people dancing, those crying, and others frozen in place.

One of the Peace Mothers I approached said, “We weren’t expecting this, of course. Maybe those who read books understand better what these words truly mean. But my daughter, I am a mother. Two of my sons died in this war. One is still in the mountains. I want nothing but peace. If this is what’s best for us, let my son come home, and let me take my last breath by his side.”

In the crowded square, even people who accidentally bumped into each other stopped to embrace. A young woman was trying to console her mother and aunt. As we spoke, I learned that both crying women had children in prison.

For her family, this moment offered a glimmer of hope. “Some people left this place happy, some left heartbroken,” she said. “We don’t even know how to feel, but maybe this means there will be amnesty for political prisoners. I’m 27 years old. I’ve been hoping for as long as I can remember. My mother, my aunt, my grandmother, even my great-grandmother—they all spent their lives hoping. What can we say to them now?”

A shared sentiment: desire for an honorable peace

The crowd carried both hope and unease. Many had not forgotten the previous peace process, what followed, the appointment of state trustees, and the imprisonment of political figures. At the same time, there was a deep yearning to see their decades-long struggle finally rewarded with lasting peace.

As they processed the sight of Öcalan’s first photograph in years and the weight of his call, some Diyarbakır residents recalled the events of Sur and Cizre in 2015 and admitted they felt “uneasy.” Others viewed this as the beginning of a new chapter.

Yet, despite all these mixed emotions, one sentiment united everyone leaving the square: the desire for an honorable peace. (ED/VK)

Kurds celebrate Newroz in Diyarbakır with massive attendance

Q&A with Salih Muslim on Syrian Kurds' deal with Damascus: 'We'll not give up our gains'

Women's Day marked in Diyarbakır with message from Öcalan

BEHIND THE CURTAIN: FİSKAYA

Besra's home

BEHIND THE CURTAIN: BENUSEN

Yeliz's home