Being A "Foreign" Journalist in 90's Turkey

Last week the police in Diyarbakir took a Dutch journalist, Frederike Geerdink, for questioning and let her free after a couple of hours. Reading that news brought me back to the 90’s when I lived and worked in Turkey as a journalist for Finnish Broadcasting Company. Then working with anything to do with the Kurdish issue could mean trouble; arrest, confiscation of material etc. For some time it looked as if those dark days of 90’s would be over forever – but it seems not, unfortunately.

Some of my clearest memories from my eight years in Turkey include killings of many Turkish and Kurdish colleagues and on the other hand gatherings in Istanbul DGM or support for other Turkish and Kurdish colleagues charged for ”doing terrorist propaganda”.

When traveling in the South-East, the plain clothes policemen were almost always following us. Being from the foreign press was sort of being an enemy for the authorities regardless if they anybody knew what for example wrote in my stories. That was not the time of the international satellite TV channels or the internet, still the authorities seemed to be sure the foreign press was there to hurt the country. Despite that we foreigners were seldom insulted physically; it seemed that the authorities knew it would mean more trouble than it would be worth.

When traveling in the South-East, the plain clothes policemen were almost always following us. Being from the foreign press was sort of being an enemy for the authorities regardless if they anybody knew what for example wrote in my stories. That was not the time of the international satellite TV channels or the internet, still the authorities seemed to be sure the foreign press was there to hurt the country. Despite that we foreigners were seldom insulted physically; it seemed that the authorities knew it would mean more trouble than it would be worth.

Only once have I had a scoop in my hands and that was taken away by the Turkish police. During the operation “Çelik Harekat” in 1995 my colleague Tom Kankkonen and I travelled to Northern Iraq and happened to be in a village, where 7 shepherds had been killed. The villagers blamed the Turkish army that had created a base nearby. Just a few days earlier Turkey had said the operation would not harm civilians and the German minister of foreign affairs, worried by the 35 000 Turkish troops on a foreign soil in Kurdish controlled Northern Iraq, had warned about troubles when the first pictures of the civilian causalities would appear in the media.

And here we were Tom and I with those pictures. Unfortunately for us also the police was aware of our footage and that was taken away from us at the Diyarbakir airport just before boarding with a promise “to be mailed to you asap.” The material was never seen again, we were taken to the police in Diyarbakir the next day and later on put into the airplane like two criminals.

My landlord was later on worried about my aims and reputation as she had red in the mainstream media with a picture and everything that I had “crossed into Iraq illegally” and was altogether a person working against Turkey. I had of course a stamp from the border and had also no other intentions than tell what had been going on in the Northern Iraq.

I was many times feeling very sorry for my Kurdish colleagues working in Turkish media in the South-East. They were always most helpful when I was visiting them in Diyarbakir; the visits in their offices would always give, except from warm welcomes, glasses of tea, plenty of laughter, also tips of stories, people and trustful taxi-drivers – but sometimes they were obviously forced to write stories about us that were not true at all. Or maybe somebody in Ankara wrote them in their names, I don’t know.

But I know that they were also always protecting me during demonstrations and other uneasy events; a foreign, female journalist would always feel safe with them, although they were also laughing at me and my fears. I was not used to guns and shootings and found it frightening if a police officer was threatening me with the bottom of his gun. “Merak etme, bir şey olmaz” [Don’t worry, nothing will happen], they used to say and I used to believe since there was no other way.

That was of course the time before the social media – even mobile phones became a daily asset only sometime in the mid 90’s. That meant that an alone traveling journalist was really alone. The phones were only the landlines, which the most remote villages did not even have – that made to work harder for both police and the press as you will read in the following example.

1993 PKK kidnapped to Finnish young men on their way to India. These two lads were driving their own vehicle and were obviously not very much aware of the political situation in the South-East. They had looked at a map and picked a road leading right into the mountainous terrain without any idea of PKK camps there between Elazığ and Erzincan.

A small delegation from Finland came to “rescue” them, Tom and I had to follow the events on the spot and behind us there was the usual police-tail. At one point we had to stay in Diyarbakir to send our stories by the phone in the hotel where as the other Finnish team looking for the kidnapped left for Elazığ. This led to our detention a few hours later on a check-point: since we were not with the other convoy we could have been somewhere in the mountains with the PKK and talking with the kidnapped.

We spent the evening in the village at the gendarme station with an officer questioning us. He got the questions by fax from somewhere and at one point he told us that one of the Finnish people in the hands of the PKK was Mr Martti Ahtipisaari. Although the name was misspelled we understood they meant Martti Ahtisaari, the Finnish president and later on a Nobel winner – somehow we could persuade the officer he and his supervisor were absolutely wrong in this matter.

Our taxi-driver had been left to go and he had phoned to Nadire Mater to tell about our arrest. Throughout the evening I heard the phone ringing and the officer answering “burda yok” [not here] – that was the answer she had been given. Somebody, in my case Nadire, always knowing your whereabouts was the only safety-net for a (foreign) journalist in those days…I never believed I would disappear “in the field”, but it always felt extremely good to know that somebody was following. I think that with today’s social media this is difficult to understand as journalists can keep their audience and bosses on track all the time online.

In the morning we were driven back to Diyarbakir to have a talk with the commander. It turned out to be a beautiful breakfast with perfectly cooked sucuk and eggs in the sunny terrace with the commander who would in fluent English sincerely apologize for the inconvenience.

Project upon project

One of the reasons I moved to Turkey was the fact that was inspired by the collectiveness of the country; that people tried together to change things into better. Whereas in Scandinavia the individualism was as its heap in late 80’s and people were going to therapy asking “how do I feel today”, in Turkey I saw people believing in moving forward together.

My entire 8 years in Istanbul I shared an office with Nadire Mater. Later on also Ertuğrul Kürkçü and Erol Önderoğlu joined us – so I really saw these civilian initiatives of the 90’s to be born and grow. I used to look with big eyes these countless big meetings about “Arkadaşıma dokunma”, “Cumartesi Anneleri”, ÖDP, “Gazetecilerin Meclisi” etc with several liters of coffee, everything covered with heavy smoke from cigarettes in our office. It was a period of projects, one after another.

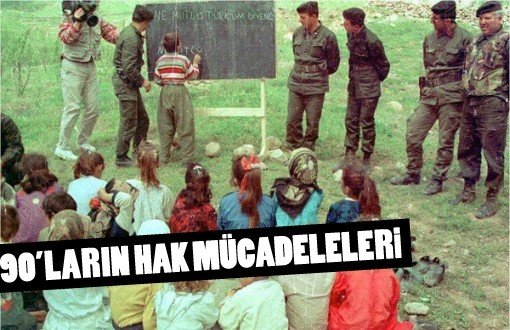

The 90’s was very violent, especially in the South-East. Still I remember it also from those initiatives and the common wish to change certain things in the society – the activists also had the belief that the struggle matters and would lead to better future.

Looking at Turkey now from the distance my question is: how is it today?

* Click here to read the article in Turkish.

PENNED BY LEENA REIKKO

Finland's Quintet Against Covid-19

LEENA REIKKO PENNED

Women, Young Politicians and Right-Wing Populists are the Winners of Finland’s Elections

LEENA REIKKO PENNED

Message by President of Finland: ‘We are Parents to a Baby Son’

After Mam Jalal

Remembering Aleppo, Their Beautiful Lives