A Smidgen of Cancer Psychology

* A sunny day last April, when I started to psychologically get used to sporting a hat (Photo: Ayfer Alkan Başer)

Director Tony Scott, who passed away last week by committing suicide, was allegedly suffering from ‘inoperable’ brain cancer. An American cancermate I follow on Twitter (@chemo_babe), could not help but react to the event, asking: why wasn’t Scott provided psychological support upon diagnosis?

Although the claim of an inoperable brain tumor was later debunked, what Americans don’t know is: thousands of cancer patients in Turkey try to get treatment without receiving a smidgen of psychological support. It’s all about oncology around here.

I discussed this issue with one of Turkey’s rare psycho-oncologists, Zeynep Armay. It turns out that psycho-oncology is a whole discipline that lies under consultation-liaison (CL) psychiatry and provides support to cancer patients, their relatives and the treatment team.

Psycho-oncologists play a crucial role in cancer treatment in the USA and in Europe, joining the medical team straight after the illness is diagnosed. It’s not like there isn’t any corporate-level work being done in this field in Turkey. The 13th World Congress of Psycho-oncology held last year in Antalya district made a big contribution in this regard.

One of CL and psycho-oncology’s basic principles is that it treats medicine and psychiatry, or biological sciences and behavioral ones holistically. In other words, it suggests we see health as a whole, with its physical and mental aspects. So psycho-oncology sets off with the assumption that the body cannot recover if the mind does not, and vice versa.

According to psycho-oncologist Armay, a ‘meteor hits’ the life of a person diagnosed with cancer, if you will. The trauma causes an initial shock, a freezing-up, inability to believe, denial, anger and depression. The process of acceptance and adaptation starts to develop after much strife. Armay adds: ‘This reaction of cancer patients to their diagnosis is perfectly normal. What’s abnormal is that which the illness puts you through.’

Well, what are these abnormal changes? Armay says that the loss of health brings with it a serious ‘feeling of grief’. She states that this feeling alternates depending on the treatment phase. For instance, the patient may have mental problems due to the uncertainty following diagnosis. If surgery is needed, psychological difficulties brought on by organ loss may be of issue in the period before and after the operation (especially in cases of breast cancer).

In addition, the changes chemotherapy and radiotherapy inflict on the body (hair loss, fatigue, infection risk, etc.) have a profound effect on the patient’s psychology. For patients who have reached the terminal stage, the acceptance of death is a whole other psychological process. Apparently, according to Armay, Ege University in Turkey academically offers this kind of psychological support known abroad as ‘hospice care’. Finally, anxiety disorders may develop for fear of relapse in patients whose treatment results in recovery.

Psycho-oncologist Zeynep Armay points out that there is no single recipe in the psychological treatment of all these conditions. The mode of therapy can be individual, psychoeducational, together with family, in a group, or cognitive behavioral. Underlining the importance of psychoeducational therapy, Armay also asserts the general lack of information in our country regarding cancer treatment.

When must therapy end?

Armay states that there isn’t one answer to this question either. She says that some patients can go on with their lives forgoing psychological support as soon as treatment ends, while others leave therapy after a certain transition period. Remarking that many patients suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder after treatment, Armay adds that through therapy or a shift in the patient’s perspective, this affliction can be turned around into an opportunity for post-traumatic growth.

If you ask me, my encounter with psycho-oncology did me a lot of good, especially after a few experiences of therapy that ended in failure. On the other hand, I always knew that strong therapeutic support would influence my treatment for the better. It wasn’t in vain that I’d written in my blog: ‘a lot of cancer patients liken their struggle to a just war. Wars certainly require powerful weapons, but perhaps the greatest weapon of all is an unbreakable spirit. That way, cancer can destroy neither your self-respect, nor you.’ (BM/HK/PU)

* You can follow Barış Mumyakmaz on Twitter (@barismumyakmaz) and through his blog, and/or ask him about his cancer treatment process.

* Click here to read the article in Turkish.

“I Lost Control With Cancer And Found it Again With Running”

BARIŞ MUMYAKMAZ INTERVIEWED

“I Come From A Land Where Soccer is Women’s Game”

Meet Turkey’s Cancer Patient Inmates

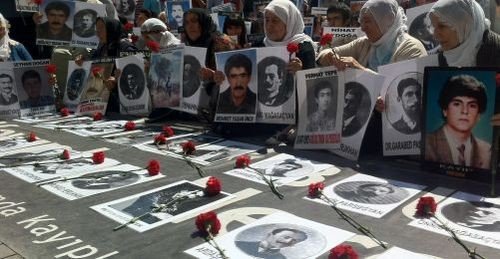

SATURDAY MOTHERS/PEOPLE

Saturday Mothers Commemorate Armenian Intellectuals of 1915

Gezi Park Emerges As Istanbul's New Alternative Hub