ÊZİDÎ WOMEN SPEAK OUT: S/HE IS MY CHILD/7

'Êzidî Women are Breaking the Mould and Remaking Their Society'

Click to read the article in Turkish

In a region where regardless of religion or ethnicity, motherhood is considered sacred, the right to motherhood has not be granted to a group of Êzidî women. Is the reason for not granting Êzidî women the right to choose whether or not to keep children born to them of rape the fact that the fathers of these children were members of a group that perpetrated a genocide on the Êzidî community or is it perhaps that these men were adherents of a different religion?

In the same way that this question has not been answered by the Êzidî community and these women whose plight has been little written about have not been granted the right to speak up for themselves, there has been little criticism of the laws and regulations that have contributed to this denial of motherhood rights and have placed these women in such an impasse.

Despite there still being many women in camps outside Iraq, religious leaders have issued statements indicating that children born outside the Êzidî fold would not be welcomed back. This and the attitude of society towards children born of rape and the mothers who choose to bring these children back with them has no doubt contributed to the truth of the statement that "There are women who have chosen not to return."

'Understanding our daughters'

I spoke to the families of two women who had not returned from the El Hol camp in northern Syria, a camp where such women form a minority, the majority being women of the ISIL kept in custody. The mother of one of these two women told me that her daughter was freed from the ISIL over a year ago, but has refused to return in order to not give up her child.

"My daughter is surrounded by ISIL sympathizers and lives in the same block as several of them in the El Hol camp. She wears a black Burqa like the others and speaks to me in Arabic over the telephone. I am worried about her safety and no longer tell her to give up her child."

She has seen several women who returned after leaving their children behind and tells me that after seeing how these women are treated by their families when they weep for the children they have left behind, has come to support her daughter's decision to not give up her child.

"In the beginning, I used to beg my daughter to give up her child and return home. She used to weep and tell me each time, 'I cannot'. I used to become angry at her even though I am a mother myself. Over time, I saw the plight of women who had returned after leaving their children behind. My heart went out to these women and it was then that I realized that my daughter was a mother too and I understood her better then."

The other woman I spoke to was Fahima, who had been taken captive together with her two elder sisters. She told me that she had no news of her eldest sister and that her other sister Rayan was in El Hol camp with her two children born of an ISIl father.

Fahima told me that she was freed from the Kayyara village in Mosul province and had left her children behind at the border between Iraq and Kurdistan when she returned and that she regretted this every day.

"I understand why my sister Rayan has chosen not to give up her children and stay on in the El Hol camp instead of returning and I support her. I live in the same camp as my elder brother who came to pick me up and bring me back and who forced me to leave my children behind. I had told him then that I did not want to give up my children and he has brought this up over and over again and constantly humiliated me for having said this."

The plight of women who gave birth to children after rape by ISIL members has indeed been brought up, but never discussed or debated. The two women above were just two of many women freed from the hands of ISIL, but have not yet returned home. There is no record of how many women are in this plight, but from what I heard and observed, this number is large.

I spoke to Khidher Domle, member of the 'Peace and Society' department at Duhok University and the General Co-Ordinator of the Duhok Support Center for Women and Children, a foundation set up with the support of the Duhok Ministry of Health and several international foundations including the United Nations Fund for Population Activities (UNFPA) on the issue of why Êzidî women with children born in captivity have been rejected by society and the current challenges facing Êzidî society.

Returning to the Êzidî Fold

Is it true that "There are women who have not chosen to return out of fear they would have to give up their children?"

From the information we have on hand, sadly, this is indeed true. NGO's working in the field in Syria tell us there are several women who after being rescued from ISIL, are still staying in camps in regions under the control of either the Syrian regime or the Kurdish Syrian Democratic Forces.

Not all of them are women with children born of ISIL fathers. There are also some women without children who have not yet returned out of concerns about the reception they would get from their familes and society.

In their five years of captivity, these women had no contacts with their family and in most cases, have not seen the news on television either. They do not know that the Êzidî community has embraced returning women and rather than blaming them for being held captive, has accepted them. Not knowing this, several women have continued to stay in the camps out of fears of being rejected and ending up in a worse situation than they are in now.

International and local NGO's are on the ground, trying to help these women return, but the scale of the problem is such that after the fall of Baghouz, the last stronghold of ISIL, several of the rescued women who were taken to the El Hol camp are still there now, not knowing where to go next.

The Male Ezidiyan Foundation has been working towards putting families in contact with rescued women and several women have been able to be reunited with their familes and have returned. This does not apply to Êzidî women with children, unfortunately. We not have numbers on this, but there are several women and children still staying in the El Hol camp. These women face not merely the possibility of rejection by their families and the society, but also severe legal obstacles. As a consequence, some of the women who returned with children left Iraq after a short while and moved abroad. Some are waiting in Iraq under uncertain circumstances waiting for the legal obstacles to resolve.

Suicide prevention

How has Êzidî society treated women who returned having left their children? And what how has it treated those who do not wish to leave their children?

This is a complex and sensitive matter. The strategy of ISIL towards the Êzidîs was similar to and a continuation of what had happened during previous Ezidi genocides. ISIL had planned on completely exterminating the Êzidî community and leaving no traces behind. Those taken into captivity were not all young women. Older women were used as servants. Young boys were given military training and used against their own community.

ISIL also planned that by by abducting Êzidî women, changing their names, forcing to them convert, buying and selling them in slave markets, they would sully these women and this would lead to the Êzidî community ostracizing these women in the future. As a war strategy, they also planned to leave these women pregnant and ensure the continuation of their own line.

In the previous genocides suffered by the Êzidîs, most abducted women committed suicide and those who did not were not accepted back into the community. However, the situation this time around was different: The community welcomed these women back and by this act, rendered the strategy of the ISIL useless.

The courage of women in speaking about the atrocities they suffered under ISIL changed previous attitudes of the community and also prevented further suicides from taking place. In the first years of the war, tragically, many women who were taken captive or who returned from captivity committed suicide. However, when some women took the bold decision of speaking out about what they had undergone changed the approach of the community and led it to embrace the women who returned. Those families who could scrape together money even paid ransoms to liberate their family members in captivity.

'Is the community ready?'

However, sadly, the community's progressive stance did not extend to accepting the children born of ISIL. The memory of ISIL atrocities is too raw and there are also laws that are in the way. The treatment of women who returned without children has been different to that of women who returned with children, but this has not led to a polarization in the community. This is because women who returned with children knew from the very beginning that their families would not accept them and have concealed their identitites.

Why do the majority of the Êzidîs not want these children? Is it because their fathers are from other ethnic and religious groups or is it because they are soldiers who committed atrocities against them?

This is an important question. However, this is not an issue that can be resolved merely by the community being ready to accept these children. When ISIL attacked the Êzidî heartland on August 3, 2014, among the fighters were Muslims from neighboring villages. Today, the fathers of some of these children born of rape to Êzidî women are these very same people, who once used to be neighbors of the families of these women. It is sad, but understandable that the Ezidi community does not want to accept these children.

In many cases, these fathers or their families know these women and children. How can the mother protect herself or her family when this is the case. And this is not the only obstacle. The community sees these children as the continuation of their fathers. And this too is understandable given the trauma this shattered community has suffered. And apart from this severe trauma, there is the issue of what the laws of the country say.

So if the Supreme Spiritual Council were to accept the children of Êzidî women back, as per the laws of Iraq, the children would be registered as Muslim. Could you tell us more about this situation.

The laws of Iraq record every child whose father is unknown as Muslim. This is not a new law and has been around for a while, but this has made the position of Êzidî women impossibe.

The result is that what Daesh could not achieve through atrocity, massacre, murder and forced conversion, is realized through legal means. There are a few women who have sought to register their children under their family records in a way that reflects what happened, but the laws do not permit it. And even worse, when the child is registered as Muslim, the mother is regarded Muslim as well.

This is to say that when an Êzidî woman brings her child back with her and wants to have it registered under her ID card, not only the child and the mother herself, but any other children she might haves even if they are from an Êzidî husband are automatically registered as Muslim. The family is thenceforth registered as a Muslim family as well. Further, the ISIL father and his family then have a claim on Êzidî property as inheritees. They can in principle come and make a claim on the child's property in the future.

This situation has been vigorously discussed in Iraq and the Êzidî community has been seeking a solution, but there has been no progress so far. The laws thus provide for a weakening of the Êzidî identity. The Iraqi government has thrown up its hands and said that they see no way out of this impasse. I think the truth is that they don't want to solve the problem.

Why?

The government is chary of recognizing ISIL as a Muslim group. The stance of the government has always been that Daesh has no link to Islam. As a consequence, the Iraqi government and its institutions do not want to address this matter to avoid sending the impression that Daesh is an Islamic group. As per the official policy, Daesh is a terrorist group, an armed group, but with no link to Islam. And this stance is a major obstacle to the resolution of this issue

A decision made by men

Did the Supreme Spiritual Council, all of whose members are men consult with women who did not want to give up their children before issuing the proclamation?

It is true that all the members of the Supreme Spiritual Council are men and yes, the decision was written by a group comprised solely of men. This decision was an opinion and not geared to resolving the current crisis. If the Iraqi government were open to a more liberal interpretation of its laws, the Êzidî Supreme Spiritual Council would be open to constructive engagement.

This decision as you point out was taken by men and without consultation with women, whose opinions should have been central importance. The laws of Iraq and the attitudes of society determined this proclamation. In contrast with the laws of Iraq, no Êzidî text mentions anything about what should be done if a Êzidî women were to give birth to a child whose father were unknown.

A decision made without view to a solution

No text mentions whether a mother may or may not keep such a child. There was pressure on the Spiritual Council from the radicals in the community and the laws of the country were an influence as well. The decision was unfortunately made without view to bringing about a solution.

But I think that a change in the laws could lead to a change of heart on the part of the Spiritual Council. It must be pointed out that neither Baba Seyh nor the Spiritual Council has rejected a child brought with her by its mother to date.

Despite an ongoing war and there being so may women still in captivity, was this decision not perhaps premature? Is this decision not also a threat to children with women?

You are right about this decision being premature. This decision made the lives of women still in captivity and those in camps such as El Hol who have not yet returned, in order to not give up their children. This should have been taken into consideration. The decision came against a backdrop of rumors that the Spiritual Council was going to announce that all children would be accepted into the community: While this didn't cause a great deal of unrest, a few groups started attacking this possibility and the Spiritual Council moved hastily to prevent discord. While it was unfortunate, I do not think this will be a threat to the women we have spoken about.

Bosnian Activists

Will the fate of these children, some in the Mosul orphanage and some still in Syria, come to resemble the fate of the "Forgotten or unseen children" born of rape during the Bosnia-Herzegovina war?

This question, where you compare two different communities is important from the perspective of understanding how war can split a community irrevocably. Recently, a few activists from Bosnia-Herzegovina came to visit us, activists who were themselves from among the children you mentioned. Among these activists were some who brought their mothers along and some who had been abandoned by their mothers when children.

From there narratives, it was clear that what they had experienced and what Êzidî women have suffered are very similar. The attitudes of society, the laws that made their lives impossible and profound difficulties they faced in integrating into society are similar. One important thing that came out in their narrations is that it is wrong to see this situation merely as a struggle by women to be with their children.

This is because, seen from the perspective of a mother, it is her right to not want to raise a child born of her rape. But while rejecting this child is the mother's right, from the perspective of the child, the situation is completely different.

For instance, one of the activists related to us how she found out she was a child born of rape only after reaching adulthood and of how she attempted to reach her birth mother, only for the mother to refuse to meet her. This young activist told us that despite understanding her mother's decision, she had never been able to overcome her anger at her mother's decision to abandon her. This example tells us that even as we respect a child's right to be with its mother, it is important to remember tht the mother has the right to refuse the child as well.

This visit gave us a better understanding of the position in our society of children who have been rejected as well as those who have not. Today, many women who want to keep their children with them have only been able to in foreign countries, just like many Bosnian women. Some Êzidî women have taken their children with them to countries like Germany, Canada and Australia.

I do not know how many children there are in the orphanage in Mosul or in the camps in Syria. Tragically, their fate looks like it will resemble that of the children of the Bosnian war. The true issue here is not the attitude of society or the government, but the fates of these orphaned children.

Refuge

I recently visited The Khanke and Sexhan camps where many Êzidî orphans now live and learnt from the camp authorities that an orphanage for these children will open soon. Will this orphanage also house children born of rape?

The Êzidî community has had no tradition of orphanages. With this last war, we have come to learn of this too. It is indeed true that such an orphanage will open soon, an orphanage that is being funded by various international agencies. But whether it will also house children born of rape: No one knows this. But I think that if the laws of Iraq permit it, these children will also be housed there, with their identities concealed. For the truth is that, despite their reservations about welcoming them into the community, Êzidîs feel for these children and do want to help them.

What charges are brough against ISIL members? Does Iraqi law accept rape as a war crime?

Rape committed during war is not classified as war crime under Iraqi law. ISIL members are not charged with rape during their trials. They are always tried under Article 4 of the Anti-Terror Law. This means, in turn, that they are not tried for perpetrating genocide against the Êzidîs or the rapes committed or many other further crimes.

No judge will invite any Êzidî woman to come to court and testify about what she underwent. An international tribunal and new laws are needed for listing rape as a war crime and trying ISIL militants for this crime. This is not something that will ever be done by Iraqi law or courts. Unfortunately, this issue is not even on the government's agenda.

If such a tribunal were to be convened, would women testify?

I am a researcher in the field of conflict resolution and peace building. Êzidî women, for the first time in the history of the Middle East, have broken the mold and changed the dynamics of society. It is for the first time that rape has ceased to be something that is only whispered and otherwise not spoken of. Indeed, these women have spoken about their trauma in several platforms. If such a tribunal were to be convened, I am sure these women will speak out and indeed speak out loudly and boldly. The world should listen to these women and begin the process of listing rape as a war crime.

Will Êzidî women come out against the decision of the Supreme Spiritual Council and attitudes of society? Or will they share the fate of their sisters who are still in captivity?

It is undeniable that this decision should have been taken solely by women. But please note that this decision was not just one taken by the Supreme Spiritual Council. They were pressured by the attitudes of society and the laws of Iraq. A woman's right to motherhood should not be at the mercy of societal attitudes or laws, is that not so? Adding to this is that there are several women who have brought back their children with themselves; they have concealed their identities and are waiting, hope agains hope for the situation to improve.

You asked me if they will fight against this decision. Unfortunately, these women know that even their closest relatives will not accept these children. Who will they struggle against and how? And even if they convince their families, how will they struggle against societal attitudes or face off the laws of the country?

Everyone knows these children are blameless and innocent and there is a section of the society which wants to help these children. But they do not want to accept these children into the society either. Given this, the decision to keep or abandon these children is not merely one that can be taken by the mother. In most cases, women have no choice but to do what their relatives, society and the laws force them them to do.

This is no doubt something that must be discussed and criticized. Many women became mothers during their years of captivity and suitable laws should have been passed to help them when they returned. Unfortunately, this is not on the agenda even now. If the appropriate laws had been passed, the women would have been freer, if they wished, to stand up to their families and society.

Will the Êzidî women, who have chiefly been known as victims of horrific crimes have a role to play in the rebuilding of Êzidî society?

This is an important question, yes, Êzidî women came to the world's attention owing to the crimes and trauma they suffered. But today, they are fighting against ISIL in Iraq, which has the weakest civil society of any country in the world. They are in the frontline of the effort to rescue women still in captivity.

Many of the women who participated in the rehabilitation program I am affiliated with are in different positions in places around the world. Several women whose education was interrupted are now in university. The woman you met earlier today returned from captivity seven months ago and is now working as a volunteer at a foundation working to uncover mass graves.

And the place where these excavations are ongoing is the place where she was herself held captive, Mosul. The woman who was with her was instrumental in rescuing her four sisters from captivity and is now working to locate and rescue other women as well as towards setting up an NGO focused on women's affairs. I do not know if the world will see them and acclaim them for this but these women are remaking Êzidî society even as we speak. (NK/SD) (THE END)

Êzidî Women Speak Out: 'S/he is My Child'

Zozan's Family: You Have No Choice But to Give up Your Child for Adoption

Meyrem: We are Left With No Choice But to Leave for Afa

Two Sisters, Fahima and Rayan and Their Cousin Seher

Leyla: The Only Thing That Keeps me Going is the Hope to See My Son Again

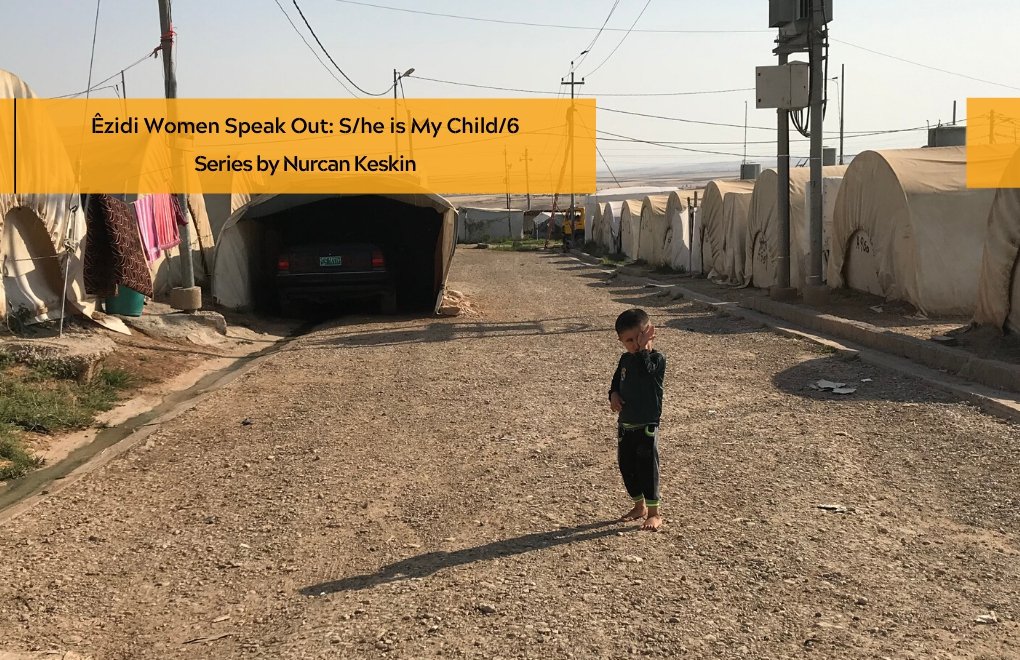

ÊZİDÎ WOMEN SPEAK OUT: S/HE IS MY CHILD/6

The Mosul Dar Al-Zahur Orphanage

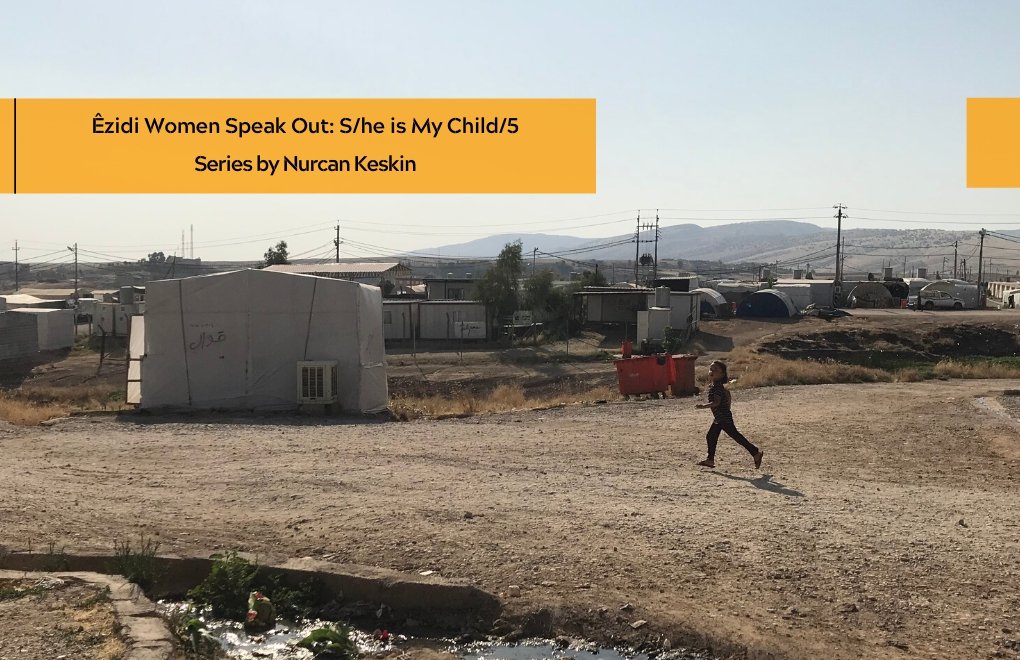

ÊZİDÎ WOMEN SPEAK OUT: S/HE IS MY CHILD/5

Leyla: The Only Thing That Keeps me Going is the Hope to See My Son Again

ÊZİDÎ WOMEN SPEAK OUT: S/HE IS MY CHILD/4

One Day with Viyan and Mizgin

ÊZİDÎ WOMEN SPEAK OUT: S/HE IS MY CHILD/3

Two Sisters, Fahima and Rayan and Their Cousin Seher

ÊZİDÎ WOMEN SPEAK OUT: S/HE IS MY CHILD/2

Meyrem: We are Left With No Choice But to Leave for Afar