When you say it again and again its effect is being lost: The weapons shall fall silent; don't let children die; let there be peace.

As long as people like Onur and Ebru are remembered as a "martyr" - the term used in Turkish for a soldier who was killed on active duty - and "guerrilla", peace will not come.

Both were born in 1990, both aged 21 -

when they died.

Both of them died in a war that started before they were even born. Both of them died during a "low intensity warfare" they were involved in on a "voluntary" or a "compulsory" basis.

One of them in Beytüşşebap in the province of Şırnak, the other one in Çukurca in the province of Hakkari (south-eastern Turkey)

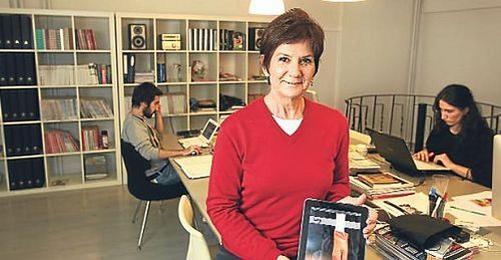

bianet editor Işıl Cinmen visited the mother of Ebru Muhikancı at her home.

"Nobody is being born a guerrilla", Birgül Muhikancı says.

On television, Ebru is mentioned as one of "24 terrorists who were allegedly killed by chemical weapons".

After that, journalist Cinmen visited the older brother of Onur Karakuş. "My mother is suffering a lot. Let's not put any more strain on her. Talk to me instead", he suggests.

Halit Karakuş talked to bianet editor Cinmen, about his brother who wrote on facebook one day prior to his death, "This is Beytüşşebap. The east is not the place of the ones who are waiting for the break of the day but it is the place of soldiers being killed on duty one day before they would have received their discharge papers".

The relatives of these two people tell us who is hurt the most by the pain of this war.

They are paying the price for the ideas and words of others and for the ones who envision a solution.

"I have not read this letter once in three and a half years"

Birgül Muhikancı lives in a small house on the outskirts of Istanbul. She has four children. One has died, one is still a baby, one is in high-school and the other one is getting ready for military service. Her son had said, "I will not go to the military as long as my sister is out there". Now he will go.

Ebru was born in Kars and raised in Istanbul.

Despite the reluctance of her father, her mother insisted on a university education for her daughter. She was accepted at the department of business in Kars. So she returned to the city she was born in and stayed with her aunt.

Also her aunt is present during the interview.

"People make parties when they turn 18, she went to prison", her mother Birgül recalls.

She was member of a students' association and arrested under allegations of "propaganda" because of the magazine published by the association. She was released after 45 days.

"That was the examination time. She came to the exams handcuffed and accompanied by the police. The handcuffs were removed only after the whole class had seen it. She was still a child, her pride was broken. She became isolated after that. She was released from prison on 16 February. She must have taken her decision to go between 16 February and 24 June. She did not tell anybody."

In the morning of 24 June, she said, "I am leaving early because I have an exam" and she never came back.

Her mother went to school to look for her but there was no exam. She understood that her daughter had left. Four days later, she received a letter.

"Maybe you will be angry, maybe you will accept it but I had to go. My brothers and sisters should study", Ebru wrote.

Her mother did not have another look at the letter for three and a half years. After having received the letter, the family did not get any news from their daughter till 27 October 2011.

"Revenge for what?"

"This is such a war that makes everybody feel the same, no matter if your child is on the mountains [in one of the hideouts of the outlawed Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK)] or in the army. I was always waiting for news. A relative of a soldier knows that the army is going to inform them. We could not even count on that, I did not know how I was going to feel".

At noon on 28 October, on a Friday, a friend of Ebru's called and said, "Did you hear from Ebru? Her name is mentioned in the news flash on television".

They went to Malatya to identify their daughter.

"Chemical weapons, wasn't it? I don't know, I did not have the strength to have a thorough look. But there were no signs of bullets. She did not even have a scratch, she had burns".

They bought plane tickets and completed the necessary procedures to bring her body back to Istanbul for the funeral. Yet, when the airline got to know about Ebru's identity, the tickets were cancelled. They returned on a 850 km journey to Istanbul by car.

Birgül Muhikancı's grief is still very fresh. She is not able to talk without crying and bianet editor Cinmen gives frequent breaks. But the mother does not feel revenge.

"I don't know any mother who is able to feel revenge after their child has gone. I did not really understand before. When we buried her I said 'My God, this is unbearable, this is so difficult'. Revenge for what? What is this pain worth for?"

"These children are also my children"

Birgül Muhikancı's eldest son is going to join the military soon. He was conscripted before but he postponed saying "How can I go when my sister is out there?"

"The children there are also my children" Mrs Muhikan says and continues, "My son will go to the military. He will shoot hundreds of children and his sister. I cannot comprehend that. Our nephew is also in the military where Ebru was. I hope he was not there when she was shot, I just hope so".

While they are talking, they have a look at the photographs of Ebru. "Ever since she was a baby, she was stubborn, proud and would stand up against injustice", she remembers.

Going through the pictures, she says, "It should stop now".

"This war would stop if thirty thousand mothers would walk hand in hand"

"It is a pity for both sides. I cannot find any other solution but walking hand in hand with the mothers of the soldiers. They are the only ones who understand the price of this war. Would it not stop if thirty thousand mothers would walk together? Is our grief not the same? I cannot get used to this".

Mrs Muhikancı has a 14-month-old son. He was born right into the middle of the Kurdish question. Who knows what the future brings for him?

"As a Kurd I am sorry for the Kurdish children. He got to know death when he was one year old. A child learns what prison means before he is turning seven. Why would a seven-year-old child chant slogans? Why should he throw stones? These children are born into politics instead of toys. I do not know who is going to give an account for this".

She repeats, "The peoples do not have a problem with each other. We grew up together with Turks. There is no problem with the people of Turkey. People run away and are afraid when Kurds are being shown as the 'bogeymen'. We do not recognize each other".

At the end of her visit, Birgül Muhikancı tells journalist Cinmen, "It is always the children of the poor who die, on both sides. Write that too".

"The doorbell rang at 4.30 am"

Onur Karakuş was born in Mesudiye/Ordu on the Black Sea Coast. He came to Istanbul when he was two months old.

He did not continue education after secondary school. They were four brothers. Onur was the youngest one.

Journalist Cinmen visited a textile workshop in Çağlayan (Istanbul) where Onur used to work. She met two of his brothers: Halit and Hamit.

The talk starts at the end. Halit Karakuş recalls how they got the news about the death of their youngest brother.

"It was Sunday night, 14 August. During Ramadan. I had got up for the 'sahur' [the early morning meal eaten before starting the fasting in Ramadan]. I was waiting for the call to prayer. The doorbell rang. I aked 'Who is it?' and they answered, 'It's the police'. It was around 4.30 in the morning. That night, a fight had happened here, at the work place. I thought they came because of that fight. They said, 'Your wife should get up and get dressed as well, you will have visitors'. A colonel and a captain came. It still did not occur to me. They asked for my father and I told him he was in his hometown".

They said that Onur had been involved in an armed conflict the night before. His brother Halit thought he was in hospital. Yet he was told, "Take it like a man, your brother has died on active duty".

He had a nervous breakdown. He tried to recover since his mother should not get the news from television. They went to the house of his elder brother Hamit altogether.

"Together we went to the house of my elder brother. We were afraid to tell my mother because she has got diabetes. We woke my mother up and took her to the hospital, saying that somebody got sick. We explained the situation to the doctors and asked them to give her a tranquilizer. Only then we were able to tell her".

Onur's mother did not believe them for a long time. She is still going to the Edirnekapı War Cemetery every day. "She wants to spend every minute there. She becomes devastated and comes back home".

"What can you learn in a 75-day basic training?"

Onur had his basic military training in Manisa (western Turkey) and was then appointed to Beytüşşebap in the Kurdish-majority province of Şırnak.

"A man who does not know the mountains is fighting in the mountains. He does not know anything about darkness at night, about the land, about living in the mountains. He does not know anything about the psychology and conditions and what to do in a difficult situation. What can you learn within 75 days?" Hamit Karakuş questions.

He also did his military service in a commando unit.

"How many years are needed to do your job well?" Hamit Karakuş asked.

"This is a job too, and it is the most dangerous one. It is a job where you pay its price with your life. Onur was involved in armed conflicts 20 days after he had arrived in Şırnak. He did not know the mountains; you cannot learn anything within 75 days. You need to know the conditions of the field in order to be there. Only professional soldiers can do that".

Mr Karakuş tells journalist Cinmen what his brother Onur wrote just one day before he died: This is Beytüşşebap. The east is not the place of the ones who are waiting for the break of the day but it is the place of soldiers being killed on duty one day before they would have received their discharge papers'.

"In the last telephone conversation we had with my brother, he said, 'It is quite dangerous in these days. No-one has got any hope. We just let things slide'. He was not afraid but he knew".

Hamit Karakuş thinks that military is a lesson for life, a test about life. Then he adds, "But the lesson is meaningless if you pay its price with your life. Nobody goes to the military saying 'Let's go and kill people'. They go by saying 'Let's get the military service out of the way, I will pay my debt and afterwards I can have a look at my future'".

"You know what bothers me the most? He called and asked me for money but I did not send any because he should learn how to get by with little money. 'You do not have the luxury of spending 400 liras within 20 days' I told him. He did not say a word and I kept completely quiet. I am not able to find out whether he was offended or not. He also wanted us to take a photograph and send it to him. While we were postponing that to tomorrow, he was gone".

"People with money do not die there"

"Onur was a crystal clear, very calm and respectful person. Our faith in God is great, that gives us strength to stand it. No rich child can reach the degree of my brother. On the other hand, they are not being appointed to the place my brother was sent to. Martyrdom does not fall to any family's share. God is choosing them. The children he takes are all good children".

They are a little uneasy about the topic of paid military service. They say that people who have 10,000 dollar do not go to dangerous places and that people from private universities do not participate in armed conflicts.

"Now paid military service came up. Probably 70 percent of the soldiers doing their military service in the commandos in the East and South-East are high school graduates and the others have finished high school. The ones with money do not die there. I have never heard of a young person who went to a private university and died on active duty".

"How did my brother give his life for his motherland? Was it because he was not rich? Then either everybody should have the chance to go or nobody should go at all. Of course I don't find it in my heart that a person with a bad elbow who did his masters goes to the mountains. But this much is very unfair. I am not saying anything about paid service but it is difficult while my brother went to the mountains after one month of training".

Stressing this again and again, they say "In spite of everything".

"Nonetheless, if we can live together with Kurds here and work together with them, this is not a matter of Kurts and Turks.

"Their mothers probably did not want them to go to the mountains either. There are lives here and there. I want to shake hands with the Kurds with peace of mind. This issue should finally end". (IC/VK)