NİLAY VARDAR REPORTS

“May Peace Reign and Life Return to Normalcy”

I am back from Şemdinli, the crossroads of three countries.

We were deeply preoccupied with the question of how to find out about what was going on there since the start of the clashes, and thus we decided to set off for Şemdinli.

Official response to the ongoing battle was muted, and even if there was some explanation, that would not have sufficed for us. Realizing the inadequacies inherent in armchair reporting from Istanbul, we pushed the envelope and I hit the road off to Şemdinli to find out about the locals' take on the events surrounding them.

I did visit "the region" before, if not Hakkari itself, but never at a time when a battle was raging only a kilometer away. Feeling edgy and thrilled at once, I set on my journey.

There was a blast between Hakkari and Van a day before my arrival, and the roads were closed down as a result. Turning back only halfway through my journey was the worst prospect imaginable. I began to unwind, however, after I got off the plane in Van and took off for Hakkari. The "news process" had thus begun.

I asked the minibus driver how often the PKK (Kurdistan Workers' Party) intercepted vehicles on the road. "People say either the military or the PKK should conduct the road checks, they ought to make a decision," he chuckled.

"Don't you hold yourself back here, the doors of all the houses here are open to you," said another young woman sitting next to me. I was not hesitant on that matter anyway.

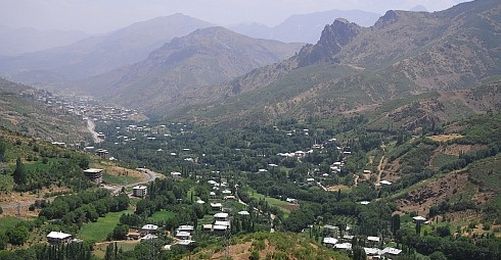

I had not fancied Şemdinli to be so lush; all the more so since there was not even a single tree standing over the mountains until we entered the district.

The moment we stepped into downtown Şemdinli, everyone began pointing toward the plumes of smoke rising from Mt. Goman and Mt. Efkar as if to say "Look, they do not believe us."

Everyone was anxious to tell me their stories because there were virtually no journalists from the mainstream media in town. İdris Emen from the daily Radikal had been there for three days, not to mention the local reporters who could not get their voices heard.

They kept asking why no journalists had come, and thus everyone was in a hurry to get their stories across just as a journalist had arrived from Istanbul.

Locals were so inured to clashes in the area for 35 years that the sounds of constant artillery fire and low flying helicopter gunships were no strangers to them. The only difference was that this was the first time around that a battle had lasted for so long.

"Adjusting" to the sound of artillery fire

I found myself in a few tragicomic situations with respect to the ever-present sound of artillery fire. You are welcome to laugh but not to jeer.

I stayed at a teachers' lodge right next to the mountain. As I was trying to fall asleep on the first night, an announcement came through a loudspeaker before the "sahur," the ritual pre-dawn meal in the month of Ramadan. The first idea that occurred to me was that they were going to order the evacuation of the village, but soon after, this was followed by the sound of Kurdish hymns. It turned out that the prohibition on singing hymns in Kurdish was lifted a year ago. It is impossible to convey the mood created by the sound of artillery fire with Kurdish hymns going in the background.

On the second night, just as I was finishing off writing the news story, the ground began to rattle. My initial thought, of course, was that a bomb was coming down on us. I leaped out of the bed and began calling out for İdris (Emen) next door. Thankfully, we came to realize that it was a temblor. We descended down and spoke to the people downstairs who were busy playing cards. Not only did we fail to convince them about the quake, however, they also kept mocking me as I had begun to snap with a jerking motion every time the artillery fired, as the shots had started off again at a very close range. I might have gotten used to the shots, but the body responds inadvertently.

No need for Kurdish

I tried to speak to as many people of all ages as possible under these circumstances. An intermediary was required at times with locals who spoke only Kurdish, but even those who knew Turkish sometimes crossed into Kurdish now and then. As I had also grown up in a bilingual household, I knew they mentioned the crucial details in their native tounge, and thus I focused on their mimics. There was no need to know Kurdish to see into the exasperation, more so than the fright, of those who were forced to leave their villages behind.

I emphasize that fear there is only valid for the children, although even they are really used to all this by now. "Enough is enough; may peace reign and life return to normalcy," was how the adults most often expressed themselves.

Most of the locals observe the Ramadan fast. Last year, they prohibited vehicles in the district center to allow for people to roam freely, and indulge in ice cream. People who go down to the district center after the "iftar" (the evening meal that marks the end of the daily fast in the Ramadan) are few and scant in number, and they see to their basic needs at day time.

I pose a simple question: "What is going on?"

"The PKK is in control beyond the mountain," everyone silently responds.

Normalcy?

What we got out of a recent meeting between the sole official authority in town, the district governor, and a delegation of deputies from the opposition People's Republican Party (CHP) who arrived in the area was that the operations were "normal."

"When I heard him say 'normal,' I felt like jumping into the middle of the broadcast and ask what was normal about this place," said once local who never got a chance to see the district governor except on television.

The locals, however, also expressed their affection for the former district governor. "He used to come out in the evening and visit the villages to have a cup of tea," they said.

Reliable information regarding the exact number of soldiers and PKK members who died in the clashes was still missing as the conflict entered its second week. Locals also said the families of soldiers would randomly call a phone number in Şemdinli to inquire about the situation there whenever a military operation was underway in the area, whether it be a market seller or a grocer they ended up talking to. There are still such families calling numbers at random, they said.

The CHP delegation also arrived in the conflict zone for the first time in the party's history to inquire about "what was really going on there." They also had rooms reserved in the teachers' lodgings from the night before, but they arrived in the morning and left toward the evening.

"Peace could come from where the conflict began"

The meeting between the CHP delegation, the mayor and the district governor was closed to the press. Once they came out, members of the delegation essentially told us they could not learn much of anything. Paying visits to evacuated villages or settlements lying inside the conflict zone was, in fact, most necessary for the delegation's purposes, and as journalists, we were also enthusiastically waiting to go there. The district governor, however, did not permit this for "security reasons," and members of the delegation did not push their chances very hard either, save for one CHP deputy from Adıyaman province in eastern Turkey.

This may be understandable, but the opposition delegation surely had not come all this way to Şemdinli to take pictures with the locals before Mt. Goman. Nonetheless, the BDP (Peace and Democracy Party) deputy, the administrators and locals all appreciated the CHP's visit.

"Şemdinli is where the conflict first began; for that reason, it could also be where the solution starts," Mayor Sedat Töre had told the delegation.

A bystander inquired about what had happened, and I told him that the CHP delegation had arrived. I had nothing more to say to him, however, when he responded "We know that; so what happened?"

Waiting for journalists to arrive

In sum, beyond all the official statements, "the region" needs journalists not for them to show the plumes of smoke rising from Mt. Goman but for them to lend an ear to its inhabitants. The prejudice that female journalists should not be sent to the region is completely misplaced, too; I encountered no difficulties whatsoever. In fact, at times I even had an easier time than my male counterparts.

Local reporters are also generous in assisting incoming journalists. Azem Demir, a Şemdinli resident, is always out and about on the streets with her camera at hand. He can even perform deep analyses based on which helicopter gunship takes off and lands where.

Local inhabitants greeted me with some surprise, as I was a female journalist. "Welcome, you are venerable," they told me. They invited me to their "iftar" meals in their homes, and I tasted their regional foods. They appeared right next to me like a bolt out of the blue to give me water to quench my thirst, even though they were fasting themselves on the Ramadan.

Their sole desire was for me to "write what we are going through."

Mele Mustafa cigarettes

There were also times we laughed under the shadow of artillery fire. Rice, tea and diesel oil comes into the region from Iraq. And then there are the "MM" cigarettes that are extremely cheap. Locals call it the "Mele Mustafa," in reference to the father of Massoud Barzani, the president of Iraqi Kurdistan. My unfamiliarity with the cheese sugar that came along with the contraband tea also led to some skepticism regarding my journalistic credentials.

My indulgence in the "Doğuve" soup that resembles the "Ayran aşı" caused some laughter, but I am not to blame. The only place where food is served in day time in the district is the hospital canteen due to the Ramadan fast; and toast is the only available item there.

Little time is left before the advent of the Ramadan holiday. Preparations typically start about three weeks ahead, but this year around, there seems to be no further meaning to the holiday than just to mark the end of the Ramadan. (NV)

Engineers Inspect Hasankeyf: Caves Damaged

Sexual, Physical Violence Against People With Disabilities Increase

Villagers on Watch in Çanakkale Against Geothermal Power Plants

Judge Replaced Ahead of Summary Judgement in Soma Trial

Most Miner Families Withdraw Complaint in Occupational Homicide Trial in Şirvan