Ex-Bank Official Hired To Sort Out The Mess

This week, Dervis, who is State Minister, sold government bonds worth 3.3 billion US dollars to local investors, as part of his austerity measures.

But, consumers, who have lost 30 per cent of their income, following the devaluation of the Turkish Lira by 30 per cent in February, appear sceptical of Dervis' programme.

Turkey's financial crisis heightened after a group of debt- burdened private banks raised interest rates from 30 per cent to 7500 per cent, forcing government to devalue the Lira.

Economists blame Turkish banking system for the woes. Triggering the crisis, the banks handed out huge loans to media moguls and supporters of the ruling parties, claims economic analyst Mustafa Sonmez.

"By the end of 2000, the losses of the state banks had already reached 20 billion US dollars, thus triggering the latest financial crisis," he says.

The 60-year-old Dervis, former deputy chief of the World Bank, has been assigned to head the government's financial recovery programme.

"Contrary to most Turkish politicians, (Dervis) is not stained with corruption. He is not from within Turkey's notorious political class, and has been in charge of the World Bank's Poverty Alleviation Programmes. All these lead to popular expectations that he will be influential in correcting Turkey's heavily distorted income distribution balances," says Professor Turkel Minibas of Istanbul University.

According to a recent opinion poll, more than 50 per cent of those interviewed believe that Dervis's programme will succeed.

However, randomly interviewed residents of Istanbul reflect a more pessimistic view of the country's economic future in the wake of the recent financial crisis.

Hale Tabakli, a 26-year-old clerk, for example, is critical of the media's exaggerations of Dervis's profile. "It would be erroneous to pin our hopes on him. He is yet to prove his ability," she told IPS.

"Turkish authorities have created the present crisis themselves. And then sought aid from a man living in the United States," says Temel Kadirli, 28, a shopkeeper, referring to Dervis.

Trade union leaders are worried that Dervis's austerity programme will increase Turkey's 20 per cent unemployment. "Three state banks have been proposed for amalgamation, and privatisation. That means at least 40,000 bank workers are going to be sacked," says Ali Riza Camci, chairperson of the Union of the Turkish Bank Workers.

"Even worse is the future of the 21,000 workers in the 13 private banks that have been proposed for liquidation," he says.

External debts also are compounding Turkey's financial woes. "Turkey is among the worst indebted countries in the world. Turkey's foreign debt hit 110 billion US dollars in 2000," Sonmez told IPS.

According to the UN Children's Fund (Unicef) report, 'Turkey's Regional Development Report 2000', 14.2 per cent of the country's population live below the poverty line, while 25 per cent lack portable water.

Workers and shopkeepers appear to be the hardest hit by the economic difficulties. According to local sources, some 10,000 small firms have closed in Turkey since February.

"Unless the new recovery schemes include such measures as dropping the inflation rates, supporting investments, subsidising exports, Turkey will become a country without small shops," says a pessimistic Bekir Duvarci, chairperson of Konya Artisans and Shopkeepers chamber.

Labour Platform, an umbrella organisation comprising trade unions, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and Farmers Chamber, has rejected Dervis's call to join hands with the government.

"Unless the government revises its economic programme in accordance with our demands, we will take to the street in April," the Platform warns.

"The country will hear our voice during the April 14 rally in Ankara," spokesperson Kaya Guvenc told IPS.

BY NADİRE MATER

We* Couldn’t Hold Our Journalism Workshop, LGBTI Events Banned; Voice and Silence

NADİRE MATER'S IMPRESSIONS

İstiklal Street 1 Day After Bomb Attack

We Are Thankful

EDUCATION

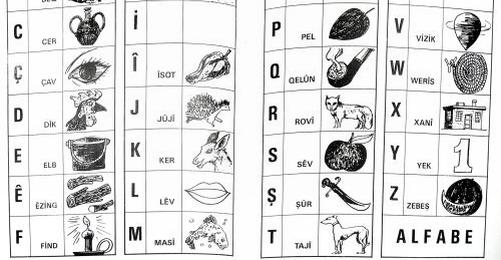

The Language Wound - Bilingualism with Kurdish

Nadire Mater Writes

The Grenade Pin that Killed İbrahim, İbrahim, Ali Osman and Mesut