Economic Plan Criticized

Announced on the weekend, the programme, which is backed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), has spawned a wave of criticisms and labour rallies at which participants are denouncing the government and its plans.

''No more lies,'' announced Kemal Dervis, the man put in charge of pulling Turkey out of its economic crisis as he unveiled the plan on Saturday. ''The Turkish people will soon know about the state's finances ... and the situation is really bad. The new programme may not give social justice today, but it will

bring social justice tomorrow.''

Dervis' statement is not only about ethical concerns, political analysts here agree. The state's finances are in such poor shape that it will take complete transparency for the Turkish public to agree to go along with the new economic recovery plan, they say.

The plan calls for a series of austerity measures which will see privatization of public sector entities, the restructuring of business sector and its integration into the global economy, the reordering the banking sector, the removal of agricultural subsidies and the cutting of public expenditure by nine

percent.

In the short term, ''no miracle should be expected'', says Dervis. ''The economy will shrink by 3 percent and the inflation rate will not be less then 55 percent, in 2001.''

The programme has already found favour with Carlo Cottarelli who heads the IMF's Turkey desk. Approval from the Fund will mean Turkey can get some 12 billion dollars in foreign aid in the coming months.

But, convincing ordinary Turks that suffering today to ensure a pain-free tomorrow is not going to be an easy task. The country has already been through failed economic recovery plans. The last programme collapsed in February under the weight of a 30 percent devaluation of the local lira against the US dollar

and volatility in the domestic market fuelled by the violent protests of thousands of small shopkeepers.

Turks were expecting better than what they got in the new recovery plan. When the 60-year-old Dervis, former deputy chief of the World Bank, was put in charge of the government's economic recovery programme in February, Turks were expecting him to produce a plan that would spell stability for the domestic economy.

According to opinion polls in February more than 50 percent of those interviewed believed that Dervis' efforts would stabilise the country.

So the shouts of outrage and disappointment were loud after the weekend's unveiling.

''Dervis' programme is no different from the previous ones. It has little chance of succeeding,'' says Suleyman Celebi, head of DISK (the Revolutionary Labour Unions Confederation).

Trade union leaders like Celebi believe that it is labour and the poor, not the ''corrupt'' financial sector, that will foot the bill for the austerity programme.

''This programme totally excludes labour. It is all about what the IMF wants,'' says Bayram Meral, the leader of Turkey's largest confederation of labour unions, Turk-Is. ''This programme includes no provisions for job creation or to prevent unemployment through public investments,'' Meral told journalists.

The country's small business sector agrees with labour about the new plan.

''This programme contains no hope for the future,'' says Sinan Aygun, president of Ankara's Trade Chamber (ATO).

''A rosy, but false scenario,'' economic analyst Mustafa Sonmez says of the new plan. ''You cannot respond to Turkey's current budget deficit of 12 billion dollars and its huge foreign debt of 112 billion dollars that equals 65 percent of the national income by simply cutting growth by 3 percent. In the 1994 crisis Turkey's foreign debt and budget deficit were half of today's yet it required the economy to shrink by 6 percent in order to recover its balance.''

''Therefore if we are not going to lie to the public. The government should admit that the economy will shrink by much more than 3 percent, that foreign loans will not be transferred as quickly and as generously as expected, and difficulties will grow in the near future,'' he said.

''A nine percent cut in public expenditure implies a zero increase in public sector salaries, salaries that have already decreased by 30 percent after the devaluation of the lira,'' Sonmez added.

Using international monitoring agencies' figures, Sonmez predicts that the inflation rate will be around 75 percent. Restructuring of the banking sector will also require that tens of thousands of employees lose their jobs. ''This programme will receive no support from labour,'' he said.

''The three major causes of the current crisis are agricultural subsidies, over-employment in the public sector, corruption and defence expenditures,'' says Can Paker, a leading businessman here. ''In order to overcome the crisis, economic measures alone will not suffice. Turkey needs profound political

reform.''

''The economic system is now practically under international control led by the IMF. And if that programme is not fully implemented Turkey will have to declare bankruptcy, and that will trigger hyperinflation finally leading to mass impoverishment and hunger.''

''Either Turkey's political class will take the lead for profound political changes to adjust the country's economy to global necessities, or a change will sooner or later be foisted upon them and then it will be very, very painfully,'' he concludes. (END/IPS/IF/IP/nm/da/01)

BY NADİRE MATER

We* Couldn’t Hold Our Journalism Workshop, LGBTI Events Banned; Voice and Silence

NADİRE MATER'S IMPRESSIONS

İstiklal Street 1 Day After Bomb Attack

We Are Thankful

EDUCATION

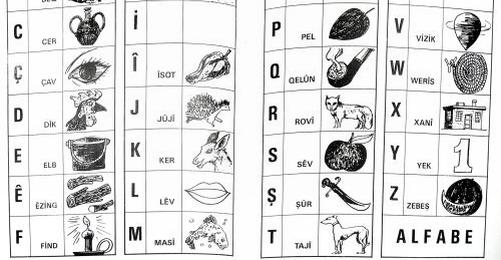

The Language Wound - Bilingualism with Kurdish

Nadire Mater Writes

The Grenade Pin that Killed İbrahim, İbrahim, Ali Osman and Mesut