Being Woman Journalist In "Islamist Country"

It was 1991, in the days of the Gulf Crisis and war when thousands of Iraqi Kurds fled their homeland to take shelter across the border. During the year, I spent most of my time there, on the Turkish and Iraqi sides of the border.

Stayed in the pro-government tribes' villages with most feared village guards, saw scores of funeral ceremonies, refugee camps filled with thousands of Iraqi Kurds. It was always cold, rainy, and very risky for a journalist.

I had been filing stories to my news agency, IPS, Inter Press Service.

At the end of the same year I had to join the correspondents meeting in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Editors were very happy about the stories from war zone. During evaluation the chief editor, believing that this would also please me said: "Everybody who reads your stories says, 'Who is this guy?'"

He had replied: "She is not a guy she is a woman?"

He was asked: "French or Italian?"

He had replied: "No, she is from Turkey."

He was asked: "What! She is a woman, she is a Turk and does it mean she is Muslim too?"

He had replied: "What I know is she is a woman journalist from Turkey, I don't know about her belief, whether she is a Muslim or not. "

I haven't reconsidered much about this anecdote, when I first heard it. However in time, it has become more and more meaningful for me since it gives a clear idea about a certain understanding.

We, the women writers and journalists of Turkey, are here, together with journalists, writers, academicians from Sweden. We are expected to speak about women of Turkey, and women journalists in particular.

Maybe we could start with apparent inequalities, which I believe more or less similar in most parts of the globe. Comprising half of the population Turkey's women hold only 4.2 percent of all 550 seats in the parliament. In the army it is even less just symbolically women are accepted in the army. The two major posts of power are the strongholds of male domination in our country.

The situation seems to have even worsened for women in the parliament as women held 4.6 of the seats in the parliament in 1935.

Women's participation in politics is high on the agenda in the election campaign for the forthcoming early elections in November. However, ironically women have found place at the bottom of the election tickets of all major, mainstream political parties, with the exception of small left wing parties, who are not expected to pass the high national election barrier of ten percent.

At home women are not in a better position, in spite of a recent series of reforms in the Turkish civil law.

According to the new legislation women and husband are equalized in every respect in domestic affairs. Women are not obliged to carry their husband's family name, they are accepted to hold an equal share on the family wealth, they are not requested of their husband's permission to work any more. Extramarital relations are now swept out of the penal code, etc.

Yet this hardly reflects the actual life for most women in Turkey's 15 million households. According to recent researches by women's studies departments of different universities, estimated one out of every three women have at least once in their lives been subject to domestic violence in Turkey.

The illiteracy rate among women are always higher, they comprise only a small fraction of modern industrial life, mostly dependent on their fathers, brothers and husbands, and as a rule an unpaid family worker for most of their lives.

Poverty accompanies, ignorance in politics and violence at home. The impact of globalization, in spite of original legends about its creating greater opportunities for humanity, has been devastating for Turkish women, as it has been for their sisters elsewhere.

Women have suffered most from privatization of healthcare and education, they have been the first on the row for massive lay offs, and equal pay for equal work has long become a dream in many sectors where women are employed most.

The recent financial crash what has hit Turkey's banking and finance sectors worst has been a disaster for the white collar women workers who comprised almost 70 percent of these sectors, while man retained their posts at the heads of the ruined firms.

The situation for Kurdish women who comprise some 14 percent of Turkey's women population is even worse. The 15 year-long bloody internal conflict in Turkey's Kurdish populated southeast regions have increased the human suffering level particularly for the Kurdish women, who have lost their beloved ones, who had been forcibly removed from their hometowns, to be dumped in the big cities.

According to official estimates 3 million people have had to flee their native villages. Half of them, the women and girls, with almost no conduct of Turkish, with no literacy, with no skill to fit modern urban life and in many cases without protection by any family member had to earn their lives in the metropolitan jungle.

Yet the job opportunities in a country with 20 percent unemployment have always been even limited for the emigrant Kurdish women. And if they ever find one they have to work for the most difficult jobs without any security and for the lowest wages and prompt to be fired any time.

However on the other side of the coin stands up a politically developed figure of the Kurdish women who during the difficult times have gained political consciousness and moved to the frontline in social struggle.

The relatively bigger women representation in the pro-Kurdish (Democratic People Party) DEHAP election ticket is an example. Women comprise 18.5 percent of DEHAP's 550 candidates for parliament. Ironically almost all of Turkey's women mayors are from among the Kurds and Arabs of Turkey.

3 women mayors govern mostly Kurdish populated district of Southeastern part of country and ethnic Arab Christian woman governs the city of Hatay in the south of Turkey.

Nevertheless the overall picture of Turkey's women is as uneven as the country itself. In some trades and professions such as medicine women comprise the majority of the workforce both as doctors and nurses, and in the social sciences in most Turkish universities the majority of the staff and students are women.

In the recent decades, Turkey's literature and art has been refreshed with the rise of a new generation of women writers and authors. Thanks to the strong impact of women's liberation movement in the late 80s the traditional taboos on women issues have been destroyed and both individual women and women's issues have gained great popularity in literature and in Turkey's intellectual life.

The number of women entrepreneurs has grown, there have remained almost no branch or industry where women are not employed or they are excluded from the top. However, still both quantitatively and in terms of influence male domination is almost the rule in every aspect of social and political life.

If we have to sum up the situation of women in Turkey is less bad in the metropolitan cites than in the countryside, among the Turks than among the Kurds, among the better educated than the illiterate, within the left-wing politics then within the right-wing.

Could we come to ourselves as journalists and compare women journalists in Turkey and Sweden? I believe there are some similarities. Women, particularly among the editorial staff and reporters comprise nearly one third of the media workforce.

Yet there exists only one-woman journalist who leads an national daily among scores of Turkey's newspapers. I hardly recall any woman chief-editor. There exists no anchorwoman. For the worse you will never see a woman's face in the white screen if she is older than let's say 40.

However in a striking contrast men have left a particular sphere of social activity to women, human rights and peace activism. Almost all activists and officers of Turkey's legendary Human Rights Association are women, yet still man have taken the lion's share in the association board for themselves and the chair is of course a man.

Saturday Mother's, naturally, could not comprise of man. This exceptional vigil, what continued for four years in Istanbul was invented, organized and led by women, and still exceptionally had a visible impact in bringing the "disappearances under custody" to en end.

I am happy to stand here and exchange my experiences with you, to convey my message. It is a very nice feeling to be heard, to be listened carefully and with affection.

Yet during all my encounters with my colleagues or with human rights activists during the last decade, I have found myself always explaining, reasoning and analyzing the situation in the East. Hardly I have found an opportunity to hear the difficulties and particularities of my colleagues from the West.

I wonder if you have no particularities or difficulties. I am sure you have. However, the time is limited the questions are so big that we always and up at some point within the Eastern Question.

I would like to convey a fresh example from Spain. I had the chance to join the 1st of May parade in Barcelona this year. Thousands were marching, we were shouting slogans, singing, and suddenly a women journalist targeted at me with her TV camera and asked: "Tell me what is the situation of women in Turkey"

I really can't remember what I had said then. Truly, What could I have said?

However, I think I could make a common observation for all of us as women journalists across the globe. Particularly after 11/9 the West has somehow shifted towards the East in the sense that, freedom of expression has been curtailed, limited and tied to scores of conditions under the pretext of combating terrorism.

The model "West" is now remodeling itself in line with the authoritarian practices and values generally ascribed to the east. Looking from Turkey I would like to express my very deep concern that the post -11 September practices of Western governments have a had a damaging effect on the fight for broader democracy and freedom of expression in our country as rulers point their fingers to the West and say: "Look what they are doing, you can not expect more?"

I wish we would be able to rethink this reactionary situation what surrounds all of us notwithstanding from what direction we are coming from - from the East or from the West?

Thank you!

* This is the text of a speech done in a round table, which was arranged by Swedish Pen in Stockholm in October 4.

BY NADİRE MATER

We* Couldn’t Hold Our Journalism Workshop, LGBTI Events Banned; Voice and Silence

NADİRE MATER'S IMPRESSIONS

İstiklal Street 1 Day After Bomb Attack

We Are Thankful

EDUCATION

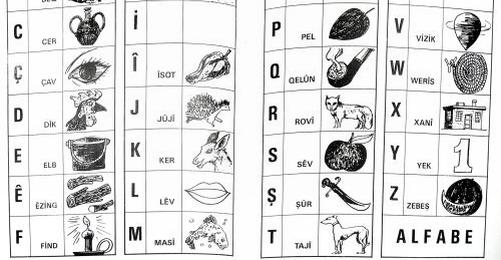

The Language Wound - Bilingualism with Kurdish

Nadire Mater Writes

The Grenade Pin that Killed İbrahim, İbrahim, Ali Osman and Mesut