4000 Media Workers Laid-Off In Turkey

The lay-offs, which began early this year, have prompted hundreds of angry journalists to demonstrate, but with little coverage in the Turkish newspapers or television stations.

''Journalists and media workers have always paid the price for the media bosses' mistakes and faults'', says Nail Gureli, chairperson of the Turkish Journalists Association (TJA).

According to Gureli, 1,000 journalists are among the 4,000 media workers who have been sacked. ''We will carry the issue to Ankara, to President Ahmet Necdet Sezer, in a bid to seek redress.''

Ziya Sonay, chairperson of the Turkish Journalists Union (TGS), whose organisation has been deserted by media workers as a result of pressure from employers, hopes that the crisis will increase journalists' awareness to re-organise. ''We are ready to provide legal assistance to our colleagues, and they should in turn regroup around the union,'' he says.

Unhappy with the existing unions, the sacked media workers have formed an ad hoc "Journalists Council Initiative" to fight their case.

One of the journalists, Nilgun Cerrahoglu says the decision to sack her was taken at an editorial meeting. "A colleague called me that my column has been removed. They fired me, and did not even bother to inform me," says Cerrahoglu, veteran journalist from Milliyet, a daily newspaper.

A reputed columnist, Cerrahoglu was praised for her weekend interviews with key figures in the country. She is now on the street looking for a job.

So are Turhan Selcuk and Bedri Koraman, both veteran cartoonists of international celebrity, and Duygu Asena, a leading feminist and best-seller novelist, all of whom had been identified with Milliyet for decades.

In order to by-pass legal obligations, employers delayed official notices of lay-off for months, coercing journalists to sign agreements to receive remunerations in installments.

''Denying compensations, and forcing journalists to sign agreements that they will receive remunerations in installments is simply unlawful,'' says TGC's Gureli, who denounced the lay-offs as 'massacre'.

Ragip Duran, who is a journalist and communications lecturer at Istanbul's Galatasaray University, believes that "political motives are behind the lay-offs."

''Media bosses justify the lay-offs with on-going economic crisis. But the majority of those who have been fired are colleagues who have resisted the wave of corruption in Turkey," Duran told IPS.

"Most of those fired are reputed for their articles and opinions challenging corruption and the political and bureaucratic powers," says Gureli.

The bulk of Turkey's mainstream media -- with more than 10 national dailies, 17 commercial TV channels, a number of radio stations, as well as weekly and monthly publications -- is controlled by a clique of business conglomerates.

Apart from a few independent newspapers with smaller circulation, business conglomerates, investing in banking, insurance, tourist industry, health and even football, own the Turkish media.

For example, the Dogan Holding, that controls Turkey's two biggest dailies Horriyet and Milliyet, another quality newspaper Radikal, two national TV stations -- CNN Turk and Kanal D -- invests in banking and finance, communications, insurance, health, oil and newspaper distribution. It is also seeking to carve out a bigger share in the proposed privatisation of the country's electric power relay systems.

Another conglomerate, the Bilgin Group, which owns a number of dailies, television stations and periodicals, also invests in the country's thriving book publishing industry, marketing, security services, insurance and banking.

The group, which owes government at least 1 billion dollars, has laid-off some 1,000 media workers at its television stations and newspapers.

''The workforce in the Turkish media is disorganised, and does not earn the same salary. While average salaries for the rank-and- file revolves between 500 to 1,000 dollars per month, senior staff is paid extraordinary salaries from 5,000 to 10,000 dollars per month,'' says Mustafa Sonmez, a journalist and economic analyst.

''Turkish media functions like an artillery shell for the business conglomerates. It comprises a powerful weapon to attack and deter others, or shield their owners from rivals," Sonmez told IPS.

With little economic and financial rationality, the media industry in Istanbul has witnessed unparalleled growth, employing some 15,000 workers, in the past decade. ''The daily circulation of the print media remains on the 1960s level of 3-4 million, while the population, which has increased two-fold, has reached 65 million," says Sonmez.

Last week the "Journalists Council Initiative", which has 500 members, met labour minister Yasar Okuyan in the capital Ankara.

Earlier, they gathered in Istanbul's Abdi Ipekci Park, named after the assassinated journalist Abdi Ipekci, who was killed by right-wing terrorist Mehmet Ali Agca in 1980. From there, they marched to Sabah newspaper, which has become a symbol of injustice and corruption for the journalists.

The changing climate among the Turkish journalist community, who in the past had least inclination for organising themselves, was apparent as hundreds marched late night under the rain, carrying torches in their hands.

To highlight their plight, the journalists have drawn up a programme for a series of protests. ''Journalists should understand that they are also workers,'' says Berat Guncikan of the independent Cumhuriyet newspaper.

Celal Baslangic, a senior reporter at the daily Radikal, has warned that the crisis in the Turkish media only hurts the public right to access to information.(END/IPS/EU/MC/LB/nm/mn/01)

BY NADİRE MATER

We* Couldn’t Hold Our Journalism Workshop, LGBTI Events Banned; Voice and Silence

NADİRE MATER'S IMPRESSIONS

İstiklal Street 1 Day After Bomb Attack

We Are Thankful

EDUCATION

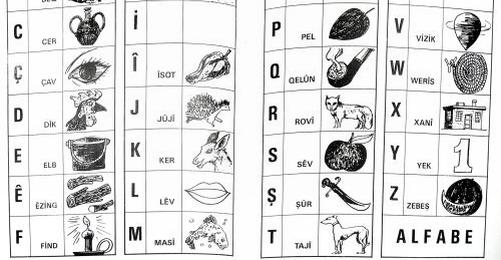

The Language Wound - Bilingualism with Kurdish

Nadire Mater Writes

The Grenade Pin that Killed İbrahim, İbrahim, Ali Osman and Mesut